Opinion

The EU is pushing Cambodia further into the orbit of China

In 2020, when the EU ended Cambodia’s preferential treatment under the ‘Everything but Arms’ trade arrangement, it cited “serious and systematic concerns related to human rights” and the need for ongoing monitoring of restrictions the governing regime was imposing on freedom of expression and political rights.

Three years later, despite troubling reports concerning the political environment in Cambodia, including the barring of opposition parties and an upswing in state-backed intimidation and arrest of dissenting citizens, the EU opted against sending a team of observers to monitor the country’s elections.

A Soviet-style pseudo-act of democracy ensued.

The country’s ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) secured a further term, and, in the weeks thereafter, a dynastic handover of power between Hun Sen and his son, Hun Manet, was formalised.

The muted response to these developments by lawmakers in the EU, the UK and the US effectively gave a three-decade-long regime, characterised by its systematic assault on civil liberties, the freedom to act as it pleases.

"We will continue to work with Cambodia's new government and will not prejudge how it may or may not perform in the coming months," a European Commission spokesperson said when pressed on how the EU would respond to Manet’s accession.

Why does this matter to Europeans?

Most obviously, the current EU position runs counter to the institution's founding, treaty-enshrined commitment to promoting democracy and human rights around the world.

It is also, in failing to keep the Cambodian regime in check, and subject to at least some level of accountability, pushing the country further into the orbit of China - a relationship that Cambodia’s young premier recently described as “inseparable”.

The significance of a deepening of relations between Phnom Penh and Beijing cannot be understated.

There is growing evidence to suggest that Cambodia is enabling China to establish a naval base at Ream, where Chinese-owned companies have been engaged to modernise the existing port. Vessels of the People’s Liberation Army appear to be permanently docked in the area, despite denials by the Cambodian government, and the two countries have recently conducted a series of substantial “Golden Dragon” joint military exercises.

Later this year, Chinese companies are due to start work on the Funan Techo canal, a 180-km, $1.7bn [€1.58bn] project, which will connect Cambodia’s capital to the Gulf of Thailand.

'Dual-use' and bypassing Vietnam

Upon completion, this project could divert traffic from the Mekong River and cut out the need for passage through Vietnam. Independent analysis of the project concluded that the canal is intended for “dual use”.

In addition to facilitating trade, the authors found the canal is designed such that it could facilitate the passage of military vessels through Cambodia, towards the Vietnamese border. In addition to these major infrastructure partnerships, Cambodia is also increasingly playing an important diplomatic, almost proxy-like role for China at major international forums, such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

This has raised questions about Cambodia’s position on key regional issues, including China’s claim to the South China Sea, which contains valuable untapped mineral deposits, as well as a thriving fishing ground. This passage is also coveted by the Philippines, Vietnam, Taiwan, and others, which have more established territorial claims.

This makes Cambodia, and other countries benefiting from China’s “Belt and Road” initiative, critical to any future powerplay in the region, in so much that Beijing’s creeping influence is not just impacting governmental but also wider public opinion.

Indeed, this year, for the first time, a poll found that a majority of Southeast Asians would choose China over the US in the event of a hypothetical war between the countries. For the West, these findings should serve as a call to action, and show that mere support for democracy in these parts is not a sufficient bulwark to China’s ambitions.

To the EU’s credit, it has set out a €300bn ‘Global Gateway’ package to help its digital, energy and transport sectors “de-risk” their relationship with China and avoid a repeat of the dependency challenges presented by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. But the reality is that action to date, in Europe, has centred primarily on shoring up domestic interests and emboldening bad actors - including Cambodia’s Manet - rather than tackling thornier, geopolitical challenges.

But this could change.

The president of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, this month secured backing from EU leaders for stinging new trade tariffs on China. Italy’s surging rightwing prime minister, Italy’s Giorgia Meloni, has withdrawn her country from the Belt and Road initiative, after public opinion became unfavourable towards on-going involvement. Even the far-right National Rally, which looks set to win the upcoming parliamentary elections in France, has struck some opposition to China’s growing influence, even if they remain silent to Beijing’s human rights abuses.

The prospect for a real shift in policy within the EU, though, comes from the newly-enlarged centre-right voting bloc in the European Parliament - the European People’s Party (EPP) - which recently stated that growing tensions in the South China Sea and the Taiwan Strait should serve as a “wake-up call for Europe”.

It has called upon the bloc to do more to foster cooperation with a “Union of Democracies” in the region. This would make for a good starting point, and speak to the EU’s self-proclaimed role as a guardian of global democracy.

But additional pressure must also be brought to bear on China’s growing network of allies, including Cambodia, where CCP-styled mechanisms for the control of public discourse, the roll-out of mass surveillance, and violent assaults on civil liberties are taking root.

It is true that the EU has a delicate line to tread with its engagements in South East Asia. However, it must also recognise that it has a role to play in protecting the fragile roots of democracy that exist in this region.

The all-carrot, no-stick approach, particularly towards the Manet regime - which has historically attempted to gain backdoor access to EU citizenship and offshore its ill-gotten assets to the bloc - is harming both the people of Cambodia and Europe’s own values and standing on the world stage.

Holding the likes of Manet to account, and insisting on his regime safeguarding social, civil and human rights should be part and parcel of the bloc’s China strategy. The consequences of sitting timidly, and failing to push back at the multi-layered system of Chinese creep could spell trouble not just for democracies, like Cambodia, but regional and wider international stability.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this opinion piece are the author’s, not those of EUobserverAuthor Bio

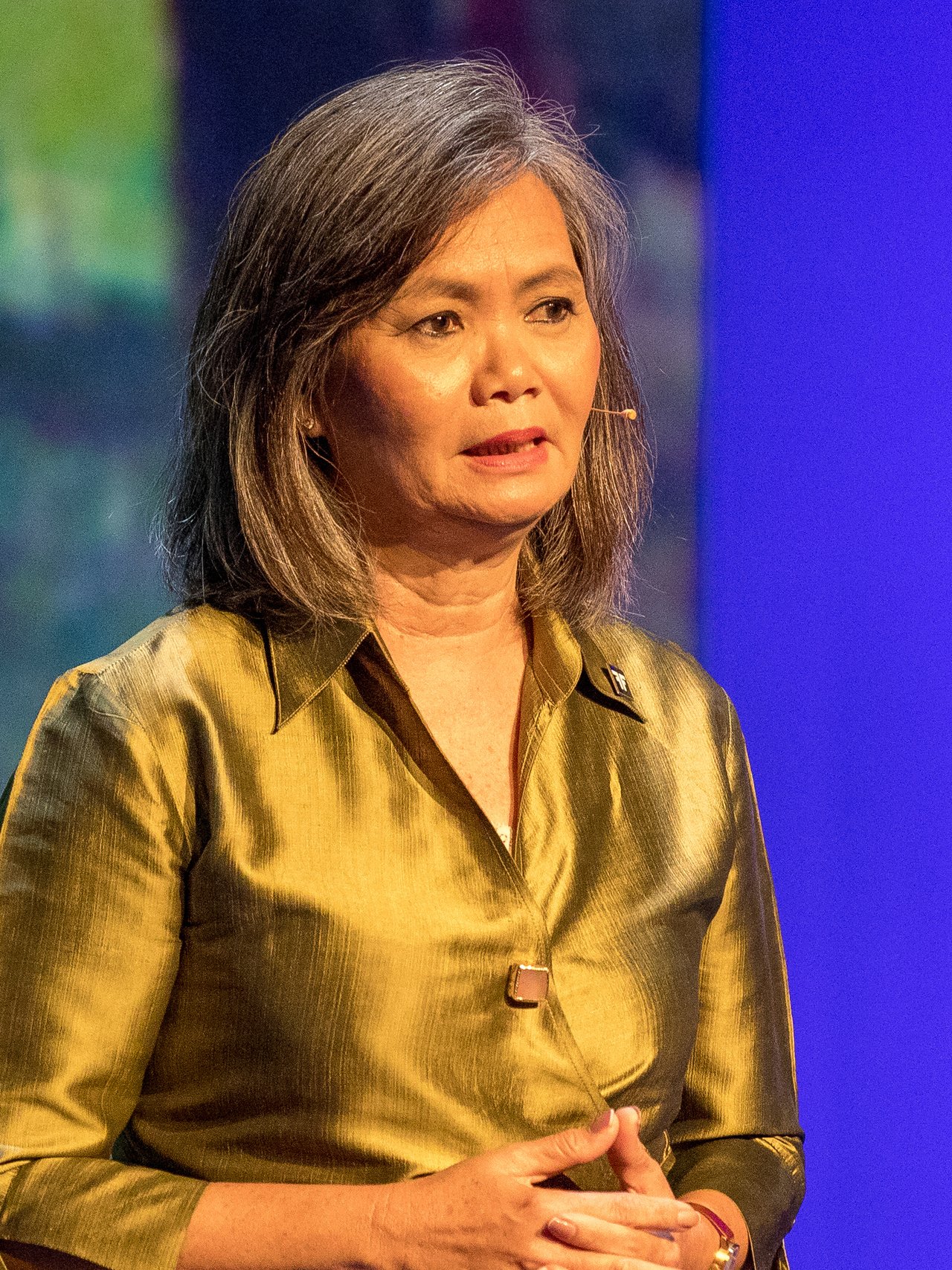

Mu Sochua is a former Cambodian politician and Nobel Peace Prize nominee now living in exile in the US, and president of the Khmer Movement for Democracy.

Tags

Author Bio

Mu Sochua is a former Cambodian politician and Nobel Peace Prize nominee now living in exile in the US, and president of the Khmer Movement for Democracy.