From welfare to 'Wild West': The man who profited from Sweden’s refugee crisis

A former darling of the progressive left in Sweden turned the 2015 refugee crisis into a lucrative business, exposing a "wild west" approach to housing people who had fled wars and persecution.

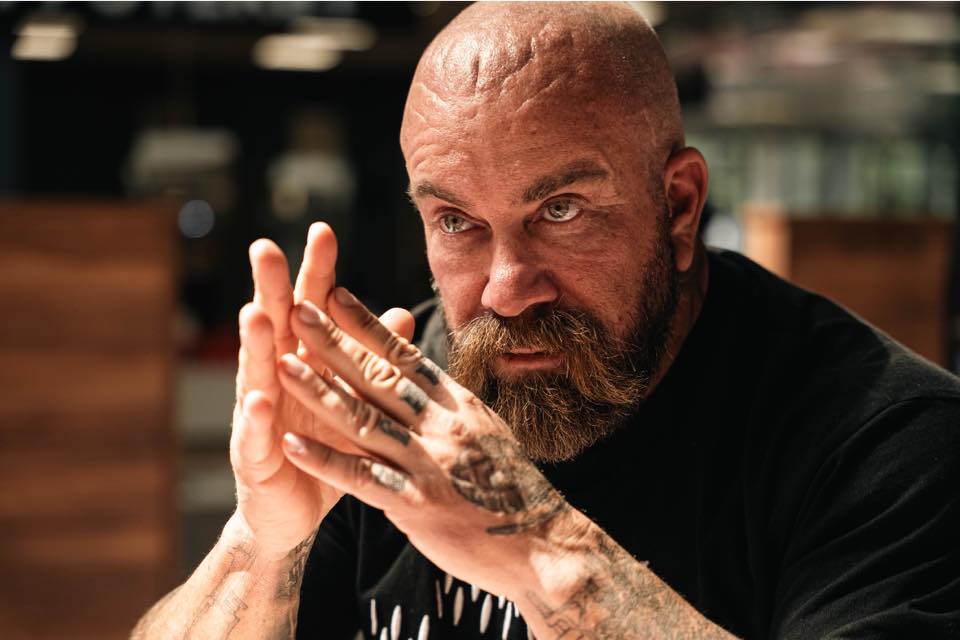

The business exploits of Jan Emanuel, a former socialist member of the Swedish parliament, have led to a soul-searching of a welfare state that gives an outward image of offering everyone high-quality publicly funded services.

But in reality, Sweden in the 2000s had already outsourced most of its welfare sector to private companies. And Emanuel's case, a reality TV star turned new-public-management capitalist, demonstrates an even deeper pivot towards the capitalisation of public services.

At one point, he became Sweden's most expensive refugee contractor, billing the state €10,000 per month per child: €2,100 for the family where the child was staying.

The "gold rush" money-making exploits were clear.

As Sweden grappled with some ten thousand people arriving every week during the fall of 2015, the opportunities to outsource the public services to the private sector exploded.

It was an unprecedented influx for a state that, up until then, had the capacity to take in only 2,500 per week.

The total number of refugees reaching Sweden in 2015 was 162,877, of which 70,000 were minors. Half of the minors came alone.

While Germany had received the highest number of refugees in Europe in 2015, Sweden received the most per capita.

Nobody had anticipated this. The official refugee forecast for 2015 was supposed to be lower than in 2014.

In November 2015, the Swedish government added an extra of about €1.2bn to handle the refugee crisis, while the EU contributed with €100m.

However, in the fall of 2015, there was no procurement process for the companies that would receive the refugees. There was simply no time.

A state of exception was declared, in which the country's migration agency and municipalities could buy services directly, without due diligence.

The new gold mine

But where did this money end up? Emanuel's first business was HVB-homes: care homes for homeless and runaway youth.

Youth care is the part of the welfare sector where privatisation has penetrated deepest, with 90 percent of HVB-homes being run by private contractors.

His homes were soon criticised for understaffing. One of them promised 24 hour-staffing, but in reality, the nighttime staff was Jan Emanuel himself, who dropped by once in a while.

As an MP, he'd made valuable contacts.

The circle around former Social Democrat PM Göran Persson, referred to as ”Persson's boys”, was awash with men wanting to make a quick buck, many of them securing a well-paid job in banking or lobbyism after leaving politics.

One of them was Per Nuder, often referred to as ”Sweden's most well-paid lobbyist,” who helped Jan Emanuel sell his HVB company for €2.2m, whereof Nuder's own share was €1.2m.

The company went on to become Sweden's second most profitable care company.

Jan Emanuel's time as an MP was replete with scandals. It was revealed that he had been trying to rent out his summer homes for exorbitant prices while his party was campaigning against rent gouging. He left the Swedish Parliament shortly after that.

The refugee crisis thus presented a lucrative opportunity.

'Being like Jesus was'

By the fall of 2015, he had become the most expensive refugee contractor in the country. Profits for his company soared by 9,465 percent during that same year.

In his autobiography, Jan Emanuel asserts that he runs his care homes according to a philosophy:

”Always carry the heaviest load. Be the first one to walk into the battle. A leader has to sweat more than everybody else.”

In an interview with Christian daily Dagen, he describes how ”Christianity for me is not throwing Bible phrases at people, it is being like Jesus was. Show the youth that a normal day job is an alternative to crime.”

Reality, notwithstanding, was quite another story.

At his care home outside Uppsala, where unaccompanied minor refugees were housed, crimes were reportedly rampant. Soon, the house was burned down and a 16-year old asylum seeker was arrested.

A neighbour said: ”There is no order at all... It's just gotten worse since Jan Emanuel came, this company is not serious and I'm afraid someone will die before authorities interfere.”

After having spoken to the media, the neighbour got a call from Jan Emanuel who warned her with the following words: ”I will use all legal means to make you stop obstructing our business.”

In 2021, the Health and Social Care Inspectorate had enough and banned Hoppetgruppen from running any business with refugee youth whatsoever.

Since then, Jan Emanuel has been campaigning for privatization of prisons, hoping to be the first to step in the market.

Such ideas appear to contradict his earlier years as a socialist MP in 2004, when he advocated for a voluntary approach to prisons. At the time, he had been named one of the up-and-coming ”New Leftists” in neo-liberal pundit Erik Zsiga's book Popvänstern (The Pop Left) from 2004.

From banning mink farms, saving chimpanzees from zoos and prison reform, Emanuel had morphed into a for-profit business tycoon.

He invests in real estate, spirits and the entertainment industry. He opens a bar that closes after a year – the company itself is handed over to an OnlyFans model. He goes to Cuba, boasting he will open a chain of 15-17 hotels, but ends up quarrelling with another exiled Swede over the purchase of a convertible and has after that not been seen on the island again.

He tried again to get into politics in 2024, founding a new party for the European Parliament, which only managed to raise 0,62 percent of the vote.

As the supply of refugees fades, so does Jan Emanuel's enthusiasm for them, and he jumps on the rightwing populist trend.

A frequent guest on podcasts, he declares that there are too many immigrants, and if they can't adapt, they need to get out.

He poses admiringly next to controversial British-American influencer Andrew Tate in a TV show and claims that feminists need to apologise to men. His erstwhile opinion on voluntary prison time is gone; now we need harsh punishments. He proposes to start a Swedish DOGE of which he'd be the head.

When asked about his refugee business and his profits, Jan Emanuel replies by sending questions back, such as: Have I blackmailed someone? Have I demanded that my employers pay me cash? Am I a narcissist, a pathological liar or an antisocial recluse?

Despite several attempts, he refuses to answer any questions.

Others also cashed in

A total of 278 new companies specialising in the care of unaccompanied minors were founded just in the fall of 2015. About 14 percent have registered criminals on the executive board, while some have ties to organised crime, such as the motorcycle mafia Bandidos.

Costs go through the roof. The fall of 2015 is a seller's market. The fee for placing one minor can be anything from 200 to 1000 euros per day.

”It became the Wild West,” refugee activist Sanna Vestin told EUobserver.

One company which signs a contract with the city of Göteborg is refugee giant Hero. The contract is valid for a year, but just before it is about to expire, the Operations manager of Göteborg City, Veronica Morales, renews it until 2018.

Even though the influx of refugees has all but stopped. The city of Göteborg ends up paying a total of €8.2m (€8200 a day) for empty rooms. Veronica Morales resigns and ends up with a new job at Hero.

The gold rush was finished within a year. In 2016, Europe struck a deal with Turkey and the influx of refugees waned. And so does the possibility of profits.

This story is part of a series of investigations conducted by Dutch investigative collective Spit and Italian publication Altreconomia into Europe's privatised migration market across six countries: Italy, Albania, Sweden, the Netherlands, and the UK.

This investigation was developed with the support of the EU Journalismfund.

Every month, hundreds of thousands of people read the journalism and opinion published by EUobserver. With your support, millions of others will as well.

If you're not already, become a supporting member today.

Author Bio

Kajsa Ekis Ekman, author and journalist from Sweden.

Related articles

Tags

Author Bio

Kajsa Ekis Ekman, author and journalist from Sweden.