Investigation

In deep shit: EU's massive subsidised manure problem

Once a popular kayaking destination, the upstream section of the Aura River in Pöytyä, southwest Finland, has become unrecognisable. Over the past decade, rampant plant growth has overtaken the waterway; in late summer, it’s possible to walk across the mass of irises and water horsetails without getting wet.

Despite decades of regulatory efforts, excess agricultural nutrients continue to flow into the river. A key culprit: manure runoff from the region's expanding pig farms.

Manure plays a crucial role in agriculture, serving as a natural fertiliser when spread across fields. However, in parts of Europe, manure production has surged to unsustainable levels.

In these “manure hotspots”, excessive concentrations of animal waste are found in relatively small areas. When over-fertilized farmland can no longer absorb the surplus manure, nutrients seep into the environment, causing significant environmental harm.

The situation is the most severe in the Netherlands and parts of Belgium, but nutrient runoffs from intensive animal agriculture cause problems across Europe.

European and UK livestock is estimated to produce more than 1.4bn tonnes of manure annually, and the overwhelming majority of this originates from a small group of Europe’s largest industrial farms. The sheer volume of manure production is no surprise: 82 percent of the European Union’s agricultural subsidies – a total of €45bn – go towards supporting animal-based foods like meat, dairy products and eggs.

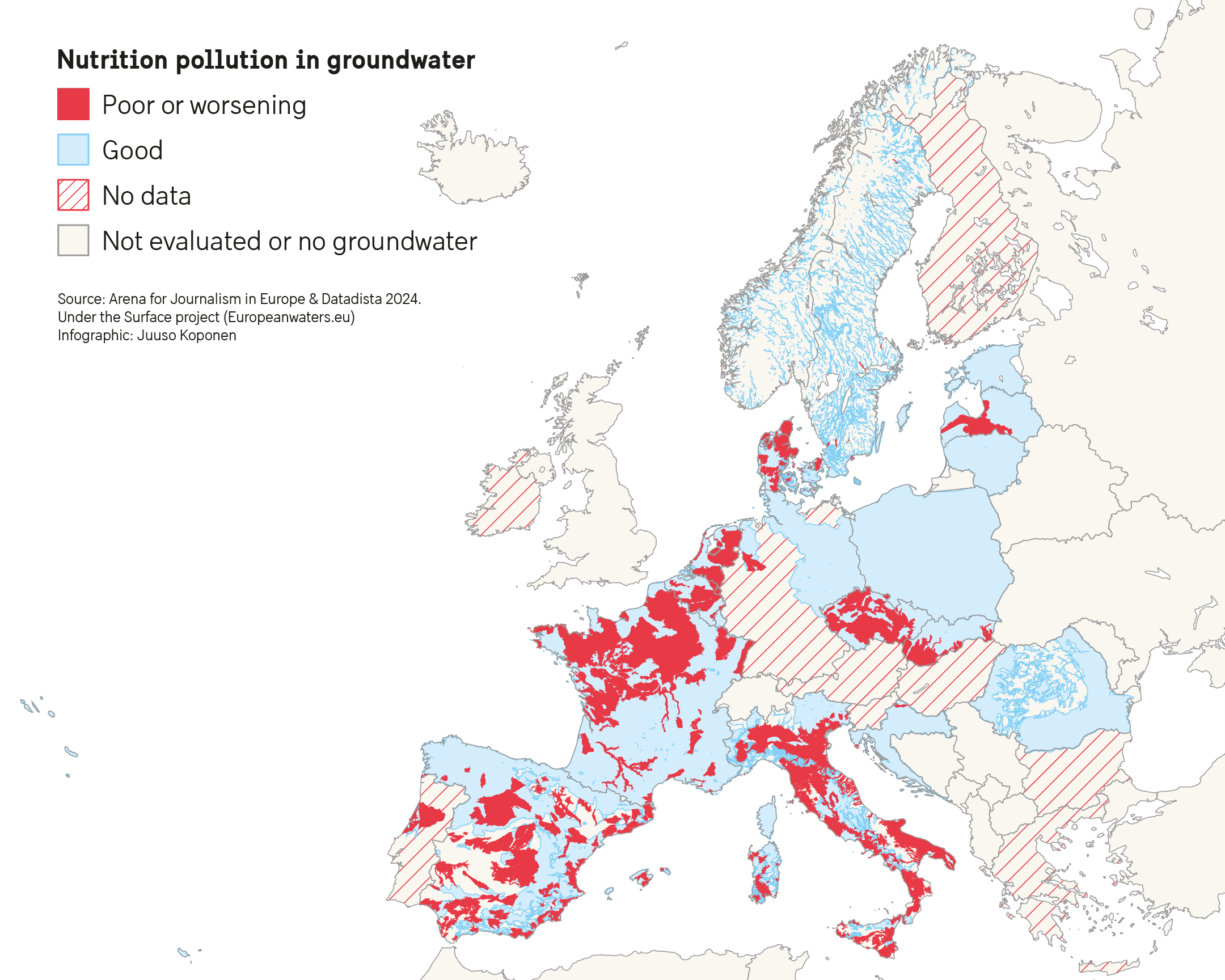

In Germany, one-sixth of its groundwater bodies are threatened by excessive nitrate pollution. In the Netherlands, the country with the highest nitrogen emissions in Europe — largely due to agriculture — nitrate levels are too high in dozens of groundwater protection areas. Nature reserves throughout the country are severely threatened by the excess of nutrients from livestock farming.

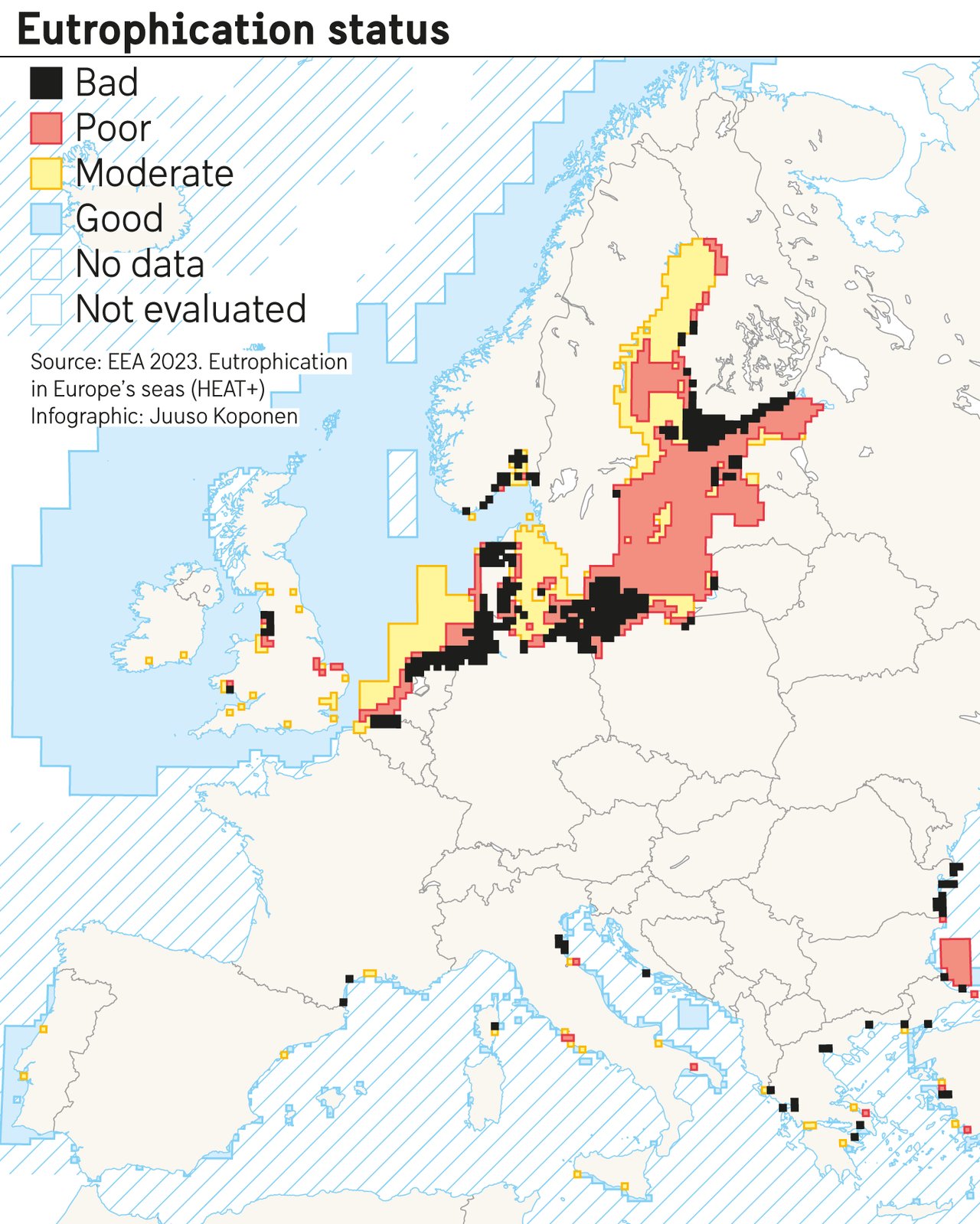

Nitrogen and phosphorus runoff from farms in Sweden, Finland, and Denmark is contributing to the eutrophication of the Baltic Sea, causing toxic algae blooms and endangering fragile marine ecosystems.

In Finland, manure management is also linked to deforestation, as farmers clear forests to create field space for spreading manure.

Relying on farmers' self-regulation

We attempted to trace where Europe’s manure excess ends up — and hit a wall. While the EU and many member states have set limits for how much manure farmers are allowed to apply in their fields, oversight is lacking. The system relies on farmers’ self-regulation, with inspections few and far between.

The lack of data is “a big dilemma”, says Frank Hilliges, a manure expert at Germany's main environmental protection agency, Umweltbundesamt [German Federal Environment Agency]. “We have no knowledge of how much nitrogen an individual farmer applies and how much of it potentially ends up in the environment.”

He adds: “The nitrogen surplus, meaning the proportion of nitrogen applied through fertilization which is not absorbed by the plants, is the central control variable in the system. It is like carrying out a tax audit without knowing income and expenditure.”

Some governments are trying to close the data gap, while others are backing away.

We have no knowledge of how much nitrogen an individual farmer applies and how much of it potentially ends up in the environment

Germany has been working on a new fertiliser law which would require farmers to report data on manure use in the future. (Currently, farmers need to make notes of how much fertiliser they are using but don’t need to report it.)

Through close monitoring, it is hoped that those farms that significantly contribute to nitrate pollution will be held more accountable. The idea behind the law is a 'polluter-pays principle', said Germany’s agriculture minister Cem Özdemir. However, the law was rejected by the Bundesrat, the upper house of Germany's parliament, in July. Farmers are already “massively overburdened by bureaucracy”, a statement by the Bundesrat said.

Finnish researchers have proposed a national database for researchers and environmental authorities to track fertiliser use across the country’s fields. Farmers already record this data, so the proposal focuses on increasing transparency and centralising existing information.

However, some farmers have opposed the proposal, saying the phosphorus status of fields is private information owned by farms. Researcher Helena Valve from the Finnish Environment Institute says there are no legal grounds for this claim. “This is critical environmental information needed for regulatory control and for determining what steps are necessary to reduce nutrient runoffs.”

The Finnish government has yet to take up the idea.

In Sweden, the government has recently proposed that farmers be required to report phosphorus levels to authorities, in addition to nitrogen.

“Agriculture is the single largest source of eutrophication, and phosphorus is the single nutrient that has the greatest impact”, says Romina Pourmokhtari, Sweden’s climate and environmental minister. “The authorities need to have more knowledge on how phosphorus is managed by our farmers.”

The EU and national governments have set limits for how much manure farmers are allowed to spread on any given field. However, without proper data, it is hard to monitor exactly what happens.

“There is no red light that flips on when somewhere someone doesn’t comply with environmental laws,” says Jeroen Candel, associate professor in food & agricultural policy at Wageningen University in the Netherlands. “The commission is regarded as guardian of the treaties, but they are limited in their possibilities to act as such.”

Nitrogen as 'national asset'?

Manure has emerged as a contentious topic in many European countries, and governments appear reluctant to accept tighter regulations.

In the Netherlands, the situation escalated into a national crisis following a landmark court ruling in favour of the environmental organisation Mobilisation for the Environment in 2019, which held the government accountable for failing to adhere to European environmental regulations.

Nitrogen emissions and the agricultural sector’s impact on natural environments have taken centre stage in the political debate for the past few years, particularly since the announcement last year that the country’s exemption from EU nitrogen regulations will come to an end.

Ireland is currently still exempt from tighter EU pollution limits. Last month, Irish prime minister Simon Harris defended the nitrate derogation, saying it was “a national asset” and “an important part of our farming infrastructure”, reported DeSmog.

In Germany, rather than changing national fertiliser legislation and risking the anger of farmers, the government risked millions of euros in fines from the European Union for violating the EU nitrates directives.

After a decade-long back-and-forth with Brussels, Berlin introduced a series of new regulations in 2023, and the EU Commission decided to drop the court case.

The nutrients in animal manure could, at least in theory, help reduce Europe’s reliance on fossil-based fertilisers, a substantial amount of which are imported from Russia. According to the a draft directive from the EU Commission, the use of manure-based fertilisers “could reduce farmers’ exposure to volatile mineral fertilizer prices and close nutrient cycles.”

However, experts warn that without strong political backing and massive investments in technology, transport, and processing infrastructure, a functioning market capable of managing the vast quantities of manure produced in Europe's livestock hubs is unlikely to materialise.

“Ultimately, we cannot avoid reducing livestock numbers in high-pollution regions,” says Hilliges from Germany Umweltbundesamt. He proposes to tie livestock numbers to available land. This means that farms should only keep enough animals to produce enough manure to fertilize the local fields.

For her part, Elin Röös, a researcher at the Swedish University of Agriculture, also believes that livestock numbers need to be better balanced with farm size. She proposes a makeover of the EU’s common agricultural policy (CAP).

“It is not the farmers' fault but a system error that forces farmers to have giant facilities with animals,” she says.

This investigation was supported by Journalismfund Europe.

Author Bio

Marieke Rotman is a staff writer at Investico, a Dutch platform for investigative journalism based in Amsterdam. A large part of her work focuses on agriculture and food systems.

Hanna Nikkanen is the environment editor at Long Play, a Finnish platform for longform and investigative journalism. She lives in Finland’s southwest archipelago.

Lotta Närhi is a Helsinki-based investigative journalist at Long Play. Her work covers environmental issues, with a particular focus on land use policy and forests.

Kristin Karlsson is a freelance journalist based by lake Mälaren in Sweden. She reports mainly on environmental issues and agriculture.

Katharina Wecker is a freelance journalist based in Bonn, Germany. She reports about the climate crisis and agriculture.

Tags

Author Bio

Marieke Rotman is a staff writer at Investico, a Dutch platform for investigative journalism based in Amsterdam. A large part of her work focuses on agriculture and food systems.

Hanna Nikkanen is the environment editor at Long Play, a Finnish platform for longform and investigative journalism. She lives in Finland’s southwest archipelago.

Lotta Närhi is a Helsinki-based investigative journalist at Long Play. Her work covers environmental issues, with a particular focus on land use policy and forests.

Kristin Karlsson is a freelance journalist based by lake Mälaren in Sweden. She reports mainly on environmental issues and agriculture.

Katharina Wecker is a freelance journalist based in Bonn, Germany. She reports about the climate crisis and agriculture.