Analysis

A burnt-out Europe: Is a four-day working week within reach?

Europe debates shorter workweeks as Poland pilots a four-day model without pay cuts, following mixed experiences and perspectives from the UK, France, Spain, Lithuania and Greece, balancing productivity, wellbeing and competitiveness concerns.

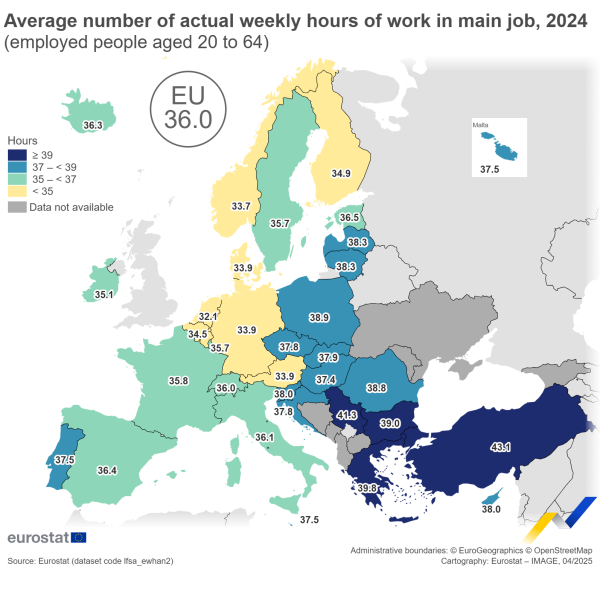

The average working week in Poland is 38.9 hours compared to the EU average of 36 hours, making it one of the most overworked nations in Europe according to Eurostat data. Now the government is trialling a four-day working week.

Last September, Agnieszka Dziemianowicz-Bąk, minister of family, labour and social policy, announced that her office had received nearly 2,000 applications from companies willing to participate in a scheme, introducing shortened working hours with no reduction in salaries.

This significantly exceeded expectations, with the department declaring that some 500 of the applications would be considered a success.

"Public and private organisations of all sizes have declared an interest. This will allow us to trial reduced working hours in various settings," said Dziemianowicz-Bąk.

Ultimately, 90 companies received funding, representing just 4.5 percent of applicants.

The ‘Shorter Working Hours – It's Happening!’ scheme will commence on 1 January 2026, with employers trialling various models of a shorter working week for 12 months.

Participating organisations must submit evaluation reviews by 15 May 2027. Based on these reviews, the government will prepare a final report and recommendations on the possible expansion of the scheme to the entire economy.

According to a statement issued by the ministry, the scheme will cover a total of over 5,000 employees.

"Interestingly, local government institutions account for half of all participating organisations in the scheme," reported the Polish media Wyborcza. "This is unsurprising, given that in many offices, a shorter working week may be more feasible to implement than in manufacturing or commercial companies, where work depends on the continuity of processes and the availability of employees on site".

The debate of a four-day working week carries with it a number of implications. Should it be Monday or Friday off? Or would it be better to limit the working day to six hours rather than working four days?

"These are all secondary considerations. The main point is to work differently, not more, due to burnout and thanks to developments in artificial intelligence," says Tina Sobocińska, founder of HR4future, emphasising the need for change for the sake of employees' health, mental wellbeing and work-life balance.

Discussions about the four-day working week are far from new.

The British way

In 2022, 61 companies operating in the United Kingdom (employing a total of almost 3,000 people) took part in a six-month experiment on a four-day working week.

The results were overwhelmingly positive. Not only did the shorter week not reduce productivity, it also significantly improved employee well-being.

As many as 71 percent of people reported a significant reduction in their burnout levels, and 39% experienced a reduction in their stress levels.

At the same time, the turnover of the companies participating in the experiment remained essentially unchanged, and even increased slightly.

Company executives were so satisfied with the results of the experiment that 92 percent of them declared they would maintain a 32-hour working week.

A frequently cited example is France, where a 35-hour working week was introduced in 2000.

In practice, however, the percentage of people working over 45 hours a week in this country reaches 13.5 percent (12.4 percent in Poland), partly due to the annual calculation of working hours rather than weekly, or by agreeing on a higher working time in exchange for a higher salary.

Spain's failed attempt

At the end of 2024, the Spanish government and trade unions announced that they wanted to reduce the working week from 40 to 37.5 hours, without reducing wages.

"The aim is for a better work-life balance while increasing productivity and efficiency," explained back then labour minister Yolanda Diaz.

According to the Spanish government, reducing working hours would facilitate the conversion of many employment contracts into full-time work, with better conditions.

Employees would gain the right to ‘switch off,’ meaning they would no longer be required to be available outside of working hours.

But opponents of the government initiative argued that it would increase costs for Spanish companies and reduce their competitiveness.

And ultimately, the Spanish Parliament rejected the bill to shorten the working week.

A different perspective from Lithuania

The debate about a shorter working week is also ongoing in Lithuania.

According to this year's survey, 67 percent of Lithuanians would like to see a four-day working week introduced in the country, while maintaining wages.

Lithuanian PM Inga Ruginiene also supports this idea. She argues that the model of reducing working hours is inevitable and will have to be widely adopted in the future.

However, there are many who argue that Lithuanians will not use their extra day off to rest, but will instead find a side job to earn more.

Therefore, some argue that raising wages would be a better solution than reducing working hours.

Another popular idea in Lithuania, well-known in Poland, is limiting the opening hours of large stores, especially shopping centres, on Sundays and public holidays.

This would give small businesses a chance to develop. Currently, some Lithuanian politicians and economists believe that large players are causing the collapse of local Lithuanian businesses.

Analyses are underway to determine whether such a solution would be lawful.

According to state authorities, this proposal may be unconstitutional, as the right to additional rest would not be guaranteed to everyone, but only to employees of large commercial companies.

Instead of four days a week, Greeks work six

An interesting European example is Greece, which has gone in the opposite direction.

According to Eurostat data, Greeks are the hardest-working nation in the European Union. Their average working week in 2024 was 39.8 hours.

However, the country’s authorities decided to go even further. Last year, Greece became the first EU country to introduce a six-day working week (48 hours per week).

These changes apply to industries and companies operating continuously around the clock, including manufacturing, energy, trade and services.

For the sixth day of work (in theory voluntary), Greeks receive additional pay, equivalent to 40 percent of their daily wage.

Moreover, last year the Greek government also decided to exclude time spent preparing before and after work from recorded working hours, resulting in an extension of working hours from eight to nine.

Nevertheless, according to opinion polls, 94 percent of Greeks would be willing to work 2.5 hours less if their wages remained unchanged.

If wages were reduced, this percentage drops, though it remains high at 78 percent.

Over 80 percent of respondents also say that shorter working hours would have a positive impact on their mental and physical health, family and social life, and individual productivity. Most also say that long working hours negatively impact their decision on whether to have children.

This is part of a PULSE collaboration between Ieva Kniukštien (Delfi.lt), Lena Kyriakidi (Efsyn), Il Sole 24 Ore. Translated by Stephen Gamage (Voxeurop). It was originally published by Gazeta Wyborcza.

Author Bio

Wojciech Podgórski (Gazeta Wyborcza), Ieva Kniukštien (Delfi.lt), Lena Kyriakidi (Efsyn), Il Sole 24 Ore.

Tags

Author Bio

Wojciech Podgórski (Gazeta Wyborcza), Ieva Kniukštien (Delfi.lt), Lena Kyriakidi (Efsyn), Il Sole 24 Ore.