Opinion

A breakdown of how the EU migration crackdown isn't working

In 2024, European leaders took credit for a drop in irregular migration.

At an October Brussels summit, EU Commission president Ursula von der Leyen declared that partnerships with third countries were working, pointing to a 64 percent decline in Central Mediterranean arrivals.

She reinforced the EU’s focus on countering people smuggling, calling it "the trigger" behind irregular migration.

Meanwhile, across the Channel, British prime minister Sir Keir Starmer has made "smashing the smuggling gangs" central to his migration strategy. He has also shown interest in European approaches, including Italy’s controversial migration deal with Albania.

In March 2025, Frontex reported a 25-percent drop in irregular migration for January-February compared to 2024. While crossings fell sharply in the Eastern Mediterranean and Atlantic, the Central Mediterranean Route saw a 48-percent increase. Frontex claims this demonstrates “the effectiveness of its cooperation with EU member states.”

But are the EU’s and UK’s external migration strategies really working? Is the crackdown on smuggling having any real impact?

These questions are tackled in our latest research report, Beyond Restrictions: How Migration and Smuggling Adapt to Changing Policies across the Mediterranean, Atlantic, and English Channel, which examines shifting migration and smuggling dynamics since 2023.

To assess this, we examined three key areas: arrival numbers, demand for irregular journeys, and the smuggling economy.

1 - Are arrivals really down? Yes — but only on some routes, and likely only for now.

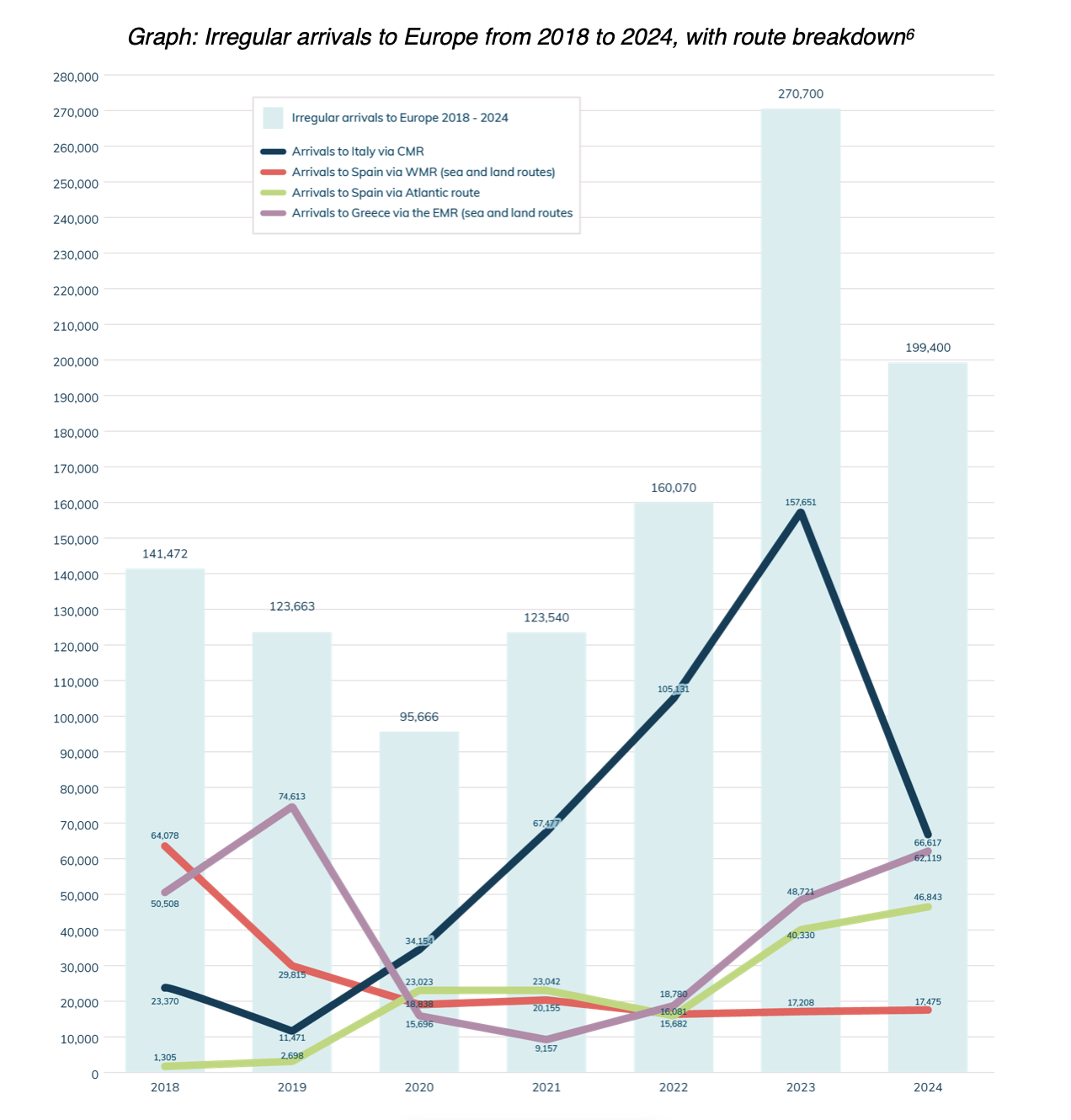

While Western and Central Mediterranean crossings dropped between 2023 and 2024, the Central Mediterranean Route (CMR) remains the busiest irregular sea route to mainland Europe. Its history of fluctuations suggests numbers could rebound — just as they did after 2017.

Meanwhile, in 2024, other routes were stable or surging:

1. Atlantic crossings to the Canary Islands were up.

2. The Eastern Mediterranean Route saw increased movement.

3. The Western Mediterranean Route remained low but stable.

4. English Channel crossings persisted despite UK and French enforcement efforts.

A temporary drop along one route does not mean migration pressure has eased—it simply shifts movement elsewhere, as seen in 2025 trends compared to 2024.

2 - Is demand for irregular journeys declining?

No. Demand remains high, and the pressures driving it are intensifying. For many, migration is not a choice but a necessity.

Worsening conflicts, persecution, and economic instability continue to push people to leave:

In the Sahel, Horn of Africa, Sudan, and across Sub-Saharan Africa, insecurity and economic hardship drive mixed migration.

1. In North Africa, political and economic instability in Tunisia, Morocco, Egypt, and Algeria fuels migration.

2. In the Middle East, conflicts sustain movement out of Syria, Palestine, and Lebanon.

3. In South Asia, Afghanistan’s dire situation forces many to leave for Turkey and Europe.

As transit countries grow more hostile and violence escalates, migration pressure toward Europe is unlikely to slow. EU deterrence policies do little to stop irregular routes. Most migrants embark on journeys with little knowledge of migration policies. Instead, they are driven by safety, economic survival, and family ties. As one migrant put it: "When choosing a destination, asylum policies barely matter. It’s about family, language, and why you left home."

3 - Has smuggling been disrupted?

No. Smuggling networks remain agile, constantly adapting to evade counter-smuggling efforts.

Crackdowns on key routes like the Central Mediterranean, English Channel, and Atlantic have made smuggling more professional and resourceful. While activity on the Western Mediterranean Route slowed between 2023 and 2024, smugglers haven’t disappeared — they’ve diversified into other crimes and can restart migrant routes when demand rises.

Despite enforcement crackdowns, our research shows that smugglers:

1. Shift routes and tactics to evade authorities.

2. Diversify criminal activities to sustain profits.

3. Exploit EU migration deals, leveraging their influence.

The smuggling economy is more complex than just criminal gangs. In Libya, coastguards reportedly accepted bribes to allow boats to depart. In Mauritania and Senegal, local fishermen step in to meet demand. In the English Channel, increased enforcement increases reliance on professional smugglers sourcing boats from farther afield. As long as demand exists, smugglers will find a way. Rather than disrupting their business, crackdowns often strengthen it.

To appear tough on migration, Europe continues striking deals with transit countries. These agreements, often worth millions, are unlikely to have a lasting impact on irregular migration. Instead, they increase human rights risks, particularly when made with authoritarian regimes, and grant transit countries leverage to use migration as a bargaining tool.

Rather than securing sustainable migration governance, these deals give EU counterparts more negotiating power. As maintaining deals grows costlier—both financially and politically—Europe finds itself pursuing new, increasingly questionable agreements.

Europe’s migration policies focus on short-term containment instead of addressing why people move. Migration is politically sensitive, and leaders feel pressured to show immediate results. Yet, short-sighted enforcement won’t stop irregular migration — it shifts routes, increases risks, fuels smuggling, and weakens Europe’s negotiating power.

To address migration, Europe needs a broader strategy, including:

A whole-of-route approach providing assistance, protection, and legal pathways along migration corridors (inspired by Safe Mobility Offices in the Americas).

1. Fast, fair, efficient asylum processing and equitable EU relocation.

2. Scalable, meaningful resettlement programs.

3. Expanded legal labour migration to meet workforce needs.

4. A functioning returns system with dignified reintegration support.

These solutions must be implemented together, not sequentially.

Waiting to “control” irregular migration before expanding legal pathways is flawed. A comprehensive migration policy must align with EU and UK trade, development, and visa policies — leveraging economic strength to safeguard human rights, rather than issuing blank checks to transit countries.

Though politically difficult, only a comprehensive strategy can reduce irregular migration and disrupt smuggling networks.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this opinion piece are the author’s, not those of EUobserverAuthor Bio

Roberto Forin is the head of Mixed Migration Centre, Europe.

Tags

Author Bio

Roberto Forin is the head of Mixed Migration Centre, Europe.