Analysis

Trump trade war could trigger financial collapse, economists tell EU

The chaos unleashed by US president Trump’s haphazard foreign policy and flurry of tariff announcements is upending the rules of global trade.

Spare a thought for Maroš Šefčovič, the EU’s trade chief who is traveling to Beijing this week for trade negotiations but had to squeeze in a last-minute detour to Washington to avert a trade war (again).

After what were described as 'intense' talks on Tuesday, he returned with little to show for it. The real question in Brussels now is: what else might be coming — and how bad could it get?

In a paper for the European Parliament’s economy committee published last week four economists sought to answer this question.

In it, they sketch out four scenarios — ranging from a low-intensity trade war with tariffs similar to those announced so far; to higher reciprocal tariffs; to a full-blown financial and monetary conflict between rival blocs — a scenario the authors describe as "trade Armageddon."

It also outlines a fourth scenario: after a shock period of high tariffs, global governments come together to forge a new economic settlement — one that rebalances trade and includes coordinated action on exchange rates and monetary policy.

Thou shalt not ‘sane-wash’

The latter mirrors the preferred outcome of the so-called Mar-a-Lago Accord, a proposal pushed by parts of the Trump administration based on a paper written last year by Stephen Miran, the chair of Trump’s Council of Economic Advisors.

It is not clear if Trump has endorsed the vision. But part of it sees the US leveraging the threat of tariffs to bring about the onshoring of US industry and tackling the twin deficits — trade and fiscal — through a reengineering of the dollar’s value and foreign investment flows.

We’ll return to the details of the proposal below.

'Nobody had Mexico and Canada getting tariffed ahead of the EU on their bingo card - and yet that is what happened'

One of the trickiest parts of analysing Trump’s policies is resisting the urge to over-interpret — or “sane-wash” — decisions and policies that are often arbitrary, constantly shifting, or flat-out incoherent.

“One cannot say with certainty that there is a logic to Trump’s trade policies,” the team of four economists write. “Nobody had Mexico and Canada getting tariffed ahead of the EU on their bingo card - and yet that is what happened.”

Still, from the chaos of the first few months, a picture begins to emerge: what started in Trump’s first term as an effort to reduce bilateral trade deficits has since evolved into a more radical project — correcting global imbalances in demand and supply, trade, and exchange rate misalignments.

This raises the prospect of much higher tariffs than under Trump 1 and could trigger more extreme forms of conflict, forcing the EU and the European Central Bank (ECB) to rethink nearly every aspect of their financial, economic, and monetary defences.

From bad to very bad

First, the potential impact. A low-intensity trade war would largely stick to measures already in place, such as 25-percent tariffs on steel and aluminium. It also assumes that existing 25-percent tariffs on Mexican and Canadian goods remain, along with 20-percent tariffs on Chinese goods.

While this would affect global trade partners, the overall impact on the EU economy would be limited, with GDP falling by just 0.014 percent.

A “high” intensity trade war scenario could result from reciprocal tariffs that factor in Value-Added Taxes. The Trump administration claims that VAT, due to its border adjustments, functions like a tariff — and has announced the Fair and Reciprocal Tariff Plan (FRTP), with a deadline set for 2 April.

This explanation is “baseless,” according to the economists. But if the US decides to treat VAT as a trade distortion anyway, it could introduce as much as 20 percent in new tariffs on all European goods.

This would lead to an estimated $200bn annual drop in EU exports to the US — equivalent to one-third of current EU goods exports to America, or about one percent of EU GDP.

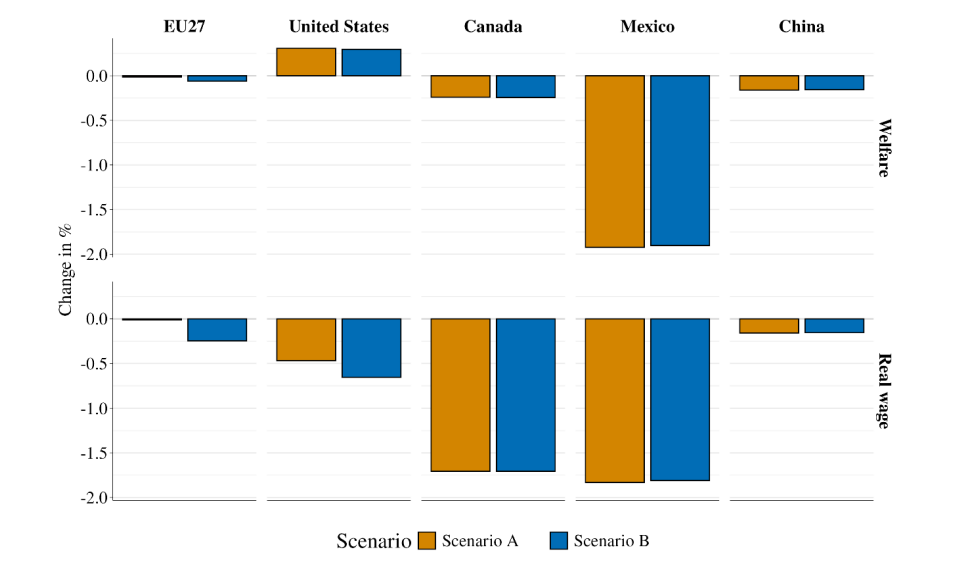

Real wages in the EU would drop by 0.25 percent. The GDP impact on the US would be positive, but due to higher cost of imports real wages would decline even more.

The overall impact of both low and high intensity scenarios would be significantly worse in both Mexico and Canada, as the above graph shows.

In short, reciprocal tariffs would be bad for everyone — including the US. That doesn’t mean they’re off the table; in fact, they’re in line with measures already introduced against Canada and Mexico and “should be taken very seriously,” the economists write.

China shock

Tariffs however could be the least of our concerns.

The US has so far relied on bilateral trade tools, but it may shift toward exchange rate policy on a broader, multilateral scale to address global imbalances — much like the vision laid out in the Mar-a-Lago Accord.

Before diving deeper, it’s worth noting that the trade imbalances targeted by the Trump administration (and others before it) are real and have been a source of concern of previous administrations.

As the world’s consumer of last resort, the US runs persistent trade deficits with almost all its trade partners — especially with China and the EU. Its role as issuer of the global reserve currency gives US consumers and businesses easy access to credit and steady capital inflows, which help finance those deficits.

ECB president Christine Lagarde described the Mar-a-Lago-Accord set of proposals as a “speculative unidentified arrangement” that “lacked substance.”

Conversely, the EU and especially China both have export surplus, with the latter trade surplus to an all-time high of just under one trillion dollars in 2024.

This brings us to the core of the global imbalance: China’s persistently low domestic consumption. While private consumption makes up nearly 70 percent of GDP in the US and just over 50 percent in the EU, in China it's below 40 percent — and falling.

Since the property bubble burst in 2021, China has redirected investment toward manufacturing, leading to massive oversupply in a low-demand economy and threatening domestic industries in Europe and elsewhere with a flood of cheap products.

Solving the imbalance requires a coherent policy and careful diplomacy, and the economists note that US and EU interests in seeing China boost domestic demand should, in theory, become “increasingly aligned.”

Mar-a-Lago Accord

Instead of coherence and diplomacy, there’s the Mar-a-Lago Accord — and Trump. So what to make of it?

Speaking in the EU parliament last week, ECB president Christine Lagarde described the Mar-a-Lago-Accord set of proposals as a “speculative unidentified arrangement” that “lacked substance.”

The idea is for foreign creditors to swap their US Treasury bonds for ultra-long-term ones — up to 100 years — with little or no interest.

That would make it cheaper for Washington to finance its debt and reduce annual bond rollovers, easing pressure on the dollar. The idea is this would increase access to private capital, allowing the US government to step back (or destroy) its national subsidy schemes.

The plan assumes no one would agree to this willingly — which is why its success relies on using tariffs and the potential withdrawal of military support through Nato as levers to pressure foreign investors and governments into compliance.

But Trump has already slapped tariffs, and his apparent friendliness toward Russia has left Nato allies questioning whether the US would actually honour its security commitments.

It weakens his leverage — and undercuts the plan it’s supposedly part of.

‘Armageddon’

So where does this leave us? “The Mar-o-Lago Accord would mine the harbour [for cash], a global-scale financial crisis would ensue,” wrote the chief economist of a German bank in a strategy paper last week.

But the economists in the document for the EU parliament warn the risks could go deeper still.

If Trump’s policies spiral into a full-blown trade war between rival blocs, a wider financial and monetary conflict could follow — what they call “Armageddon," Trump may leverage the Fed to withhold dollars from allies it perceives as ungrateful.

In this scenario, the EU should prepare for a complete collapse of the international multilateral order, with the US potentially walking away from the WTO (already on life support), the IMF, and the World Bank — steps outlined in Project 2025, the conservative blueprint that, while unofficial, has guided other Trump administration actions.

This kind of rupture could lead to a scramble for dollar liquidity, which could push the euro into the role of top global reserve currency — but in a world badly shaken by a US pullback. While not considered the most likely scenario by the economists, it’s far from unthinkable.

As Reuters reported on Saturday, some European central banking and supervisory officials are beginning to question whether they can still rely on the US Federal Reserve to provide dollar funding during a financial crisis.

A complete rethink

If the Fed weaponises dollar swap lines, or is no longer willing to be lender of last resort, the ECB could be forced to step in, by extending currency swap lines to a broader range of countries, and acting as lender and market-maker of last resort — not just for banks, but also for clearing houses, asset managers, and pension funds.

This would call for a full rethink of how the ECB operates, and “unprecedented coordination between the ECB” and national finance ministers, the economists write.

Long story short: the EU treaty doesn’t allow for the ECB to take its cue on its policies from governments. Exchange rate policy is officially set by ministers, but only the ECB can act on it, typically by buying or selling currencies.

Even then, it can only move if it doesn’t clash with its inflation mandate.

As the ECB itself noted on its website, the euro’s exchange rate “isn’t a policy target,” and interventions are rare and only happened twice in 2000, and again in 2011.

But the economists argue that the ECB should “push the limits” of what it can do and “urgently” prepare for an economic Armageddon — which, while still unlikely, is becoming “increasingly probable.”

This piece was amended to reflect the outcome of US-EU trade talks on Tuesday.

Author Bio

Wester is a journalist from the Netherlands with a focus on the green economy. He joined EUobserver in September 2021. Previously he was editor-in-chief of Vice, Motherboard, a science-based website, and climate economy journalist for The Correspondent.

Tags

Author Bio

Wester is a journalist from the Netherlands with a focus on the green economy. He joined EUobserver in September 2021. Previously he was editor-in-chief of Vice, Motherboard, a science-based website, and climate economy journalist for The Correspondent.