Opinion

The Mediterranean: where the EU’s duty to rescue ends

On 2 August 2025, the Ocean Viking, a ship chartered by SOS Méditerranée, carried out a rescue mission off the Libyan coast. Thirty-seven people climb on board. All are from Sudan, fleeing a new surge of violence, with its population falling victim to a severe food crisis.

The ship is assigned the harbour of Ravenna as a landing point, 1,600 km away from the rescue location. It’s a five-day trip, one way.

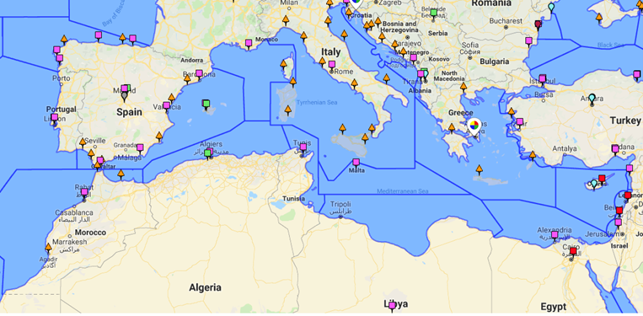

Following the disembarkment, the Ocean Viking immediately turns back to the coasts of Libya and Tunisia to resume its watch in the search and rescue zones (SAR) of the two countries. These SAR zones exceed the territorial waters of the coastal States, and break up the Mediterranean into a mosaic of rescue areas assigned to the nations lining the basin.

The zones are areas defined by maritime law as zones of legal responsibility for the coastal States, regarding patrolling, activation and coordination of rescue missions. Libya and Tunisia have proven especially deficient in this assignment, if not directly responsible for violent and illegal interventions against individuals attempting the crossing.

Only just returned to its watch area, and in the middle of the night, the Ocean Viking manages the rescue of 7 people who are immediately taken to safety on board. In the following hours, the verdict of the Italian authorities comes in: without further delay, the ship must disembark the survivors in the harbour of Ortona, this time located 1,400 km away, just across from Rome on the far side of Italy.

This repetitive scenario is the result of the Piantedosi decree, issued by Italy at the beginning of 2023. The law mandates that following each rescue operation, rescue vessels must immediately request a port assignment and disembark the rescued individuals immediately – even if further rescues could be done in the meantime.

Before its enactment, the rescue ships of INGOs could carry out successive missions, taking on passengers within the limits of the boat’s capacity.

The lack of reaction from the European Commission and Parliament to the announcement of this decree by member state Italy is disgraceful.

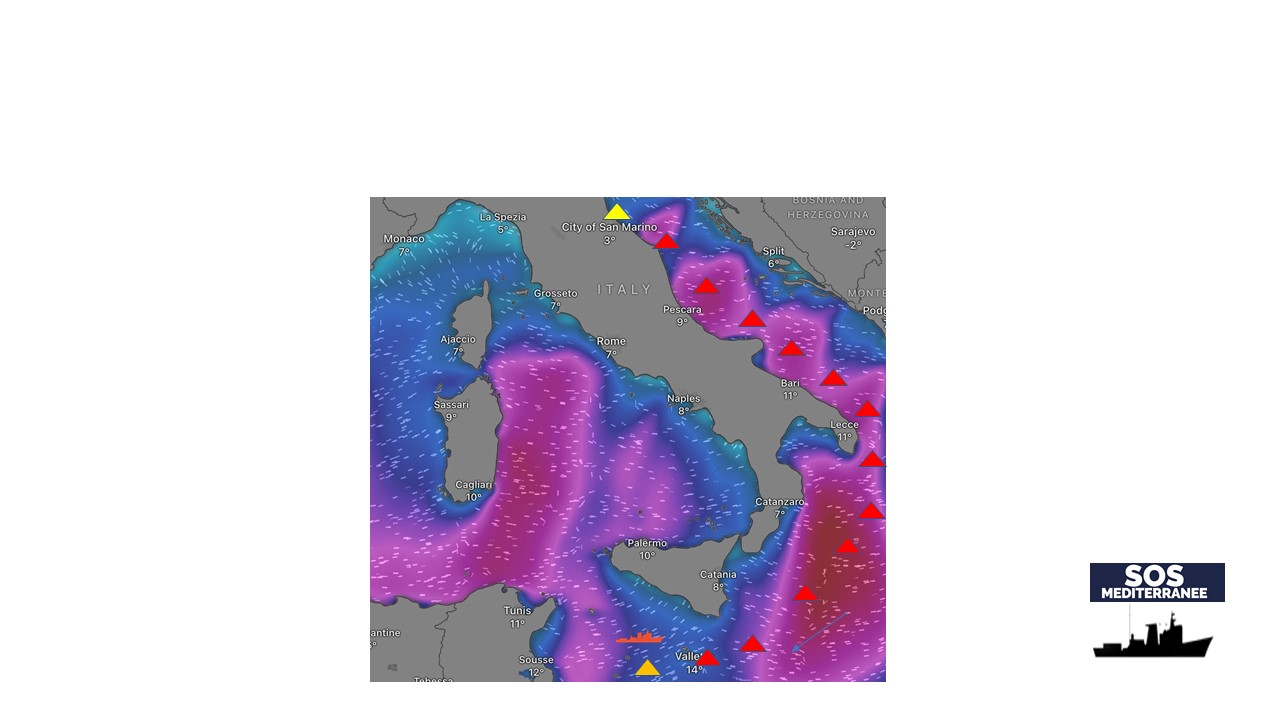

The text has been the cause of continuous restrictions and a rejection of the duty to rescue, mandated by international safety conventions. During the eight to ten days needed for a round-trip to a location dictated by no technical, medical or safety-related argument, the rescue apparatus, already famously insufficient in its means, is stripped of one of its major actors among the rare ships habilitated to respond in heavy weather. Rescue teams are forced to make huge and unnecessary journeys.

Would it also be acceptable to systematically impose on first responders in the Alps to deliver car wreck victims to hospitals in Paris?

This strategy, shamelessly condoned by the EU, demonstrates with total impunity its goal of exhausting humanitarian actors in the Mediterranean.

It leads to the burnout of the highly qualified staff alternating on board the Ocean Viking during six-week rotations, of which precious time is chipped off by the deliberate remoteness of the landing points. These professionals are committed to saving lives, not endlessly wandering at sea. They are first-responders. Sea rescuers and medical staff have no interest in the origin and motivations behind the journey of the shipwreck victims; they respond to the needs of people in mortal danger.

Rescue operations are extremely tricky, with risk factors adding up: instability and poor condition of the boats used in the gamble of the crossing; number of occupants, often sailing without a safety-vest, and therefore any movement of panic on board having catastrophic effects; weather conditions and frequent blasts of wind the Mediterranean is infamous for; undernourishment and exhaustion of the survivors, as well as frequent burn injuries sustained under the combined effect of fuel spills, salt water and sunlight exposure. In these conditions, sea rescue cannot be improvised.

Moreover, financial waste tightens the chokehold due to additional spending on fuel needed to cover the unnecessary distances. In 2024, this became an extra charge of €500,000 for SOS Méditerranée.

Italian authorities create further obstacles in some harbours, blocking the usual supply chain to the ship and preventing its access to necessities such as fuel, water or food, adding to the already mentioned logistical blocks.

Finally, Italian authorities ordered for the first time the immobilisation of one of the planes chartered (by the INGO SeaWatch) for the surveillance and scouting at sea of distressed ships, causing a wave of unanimous outrage from rescue INGOs.

This all amounts to massive waste, which fatally translates into deaths and loss that could have been prevented.

These methods must come to an end. The EU must negotiate with Italy the possibility of successive rescue missions guided by the reality of the situations faced at sea, in coordination with the harbour authorities, and with the financial support of the EU.

On 24 August, the Ocean Viking came under sustained fire from a Libyan coastguard patrol boat. Several projectiles hit the vessel. Fortunately, none of the survivors on board or the crew were injured. But this unacceptable act reflects the European Union's complicity with Libya in allowing human rights violations against migrants and refugees transiting through the country. This armed violence directly targeting a rescue vessel is a further step in the strategy to weaken the aid and testimony of humanitarian organisations providing assistance to shipwrecked people.

The potential consequences of this incident are major for the deployment of all humanitarian rescue NGOs in the Mediterranean.

That's why it's vital that the EU takes concrete actions:

1) A full and independent investigation into this attack and accountability for those responsible.

2) An immediate end to all European collaboration with the Libyan coastguard's political representatives, who were behind the attack and whose incompetence is well known.

3) An end to the criminalisation of search and rescue operations at sea, which fosters a hostile climate towards rescue NGOs and makes it possible to commit criminal acts against survivors and humanitarian teams.

What we witness today in the Mediterranean is a moral failure of the humanitarian principles the EU flaunts at international conventions, conveniently ignoring mention of the situation at its own borders. This seems to be where humanitarian concern evaporates.

Primum non nocere is the motto of rescuers. This fundamental notion could greatly benefit the EU if it were to take it to heart and practise it.

Every month, hundreds of thousands of people read the journalism and opinion published by EUobserver. With your support, millions of others will as well.

If you're not already, become a supporting member today. Use the code TRYIT to get the first month for just €4 (instead of €11), valid until August 31.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this opinion piece are the author’s, not those of EUobserverAuthor Bio

Pierre Micheletti, physician, administrator of SOS Méditerranée-France, member of the National Consultative Commission on Human Rights (CNCDH). Fred Kleinberg, painter. Sébastien Guisset, director.

Tags

Author Bio

Pierre Micheletti, physician, administrator of SOS Méditerranée-France, member of the National Consultative Commission on Human Rights (CNCDH). Fred Kleinberg, painter. Sébastien Guisset, director.