EU cashes in on €130m in rejected visa applications

EU governments rake in €130m per year in rejected visa application fees, dubbed as 'reverse remittances', according to new analysis shared with EUobserver.

The cost of Schengen visa rejections in 2023 was €130m, up from €105m in 2022, the data compiled by Marta Foresti and Otho Mantegazza at LAGO Collective finds. The total sum is likely to increase in 2024 since the visa application fee to travel to the EU will increase from €80 to €90 for adults on 11 June, following a recent decision by the EU Commission.

The UK, meanwhile, raised £44m (€50m) in rejected fees.

The fees are non-refundable, regardless of the outcome. The figures do not account for the costs incurred by not being able to travel for business and leisure, or bills for legal advice and private agencies involved in processing visa applications.

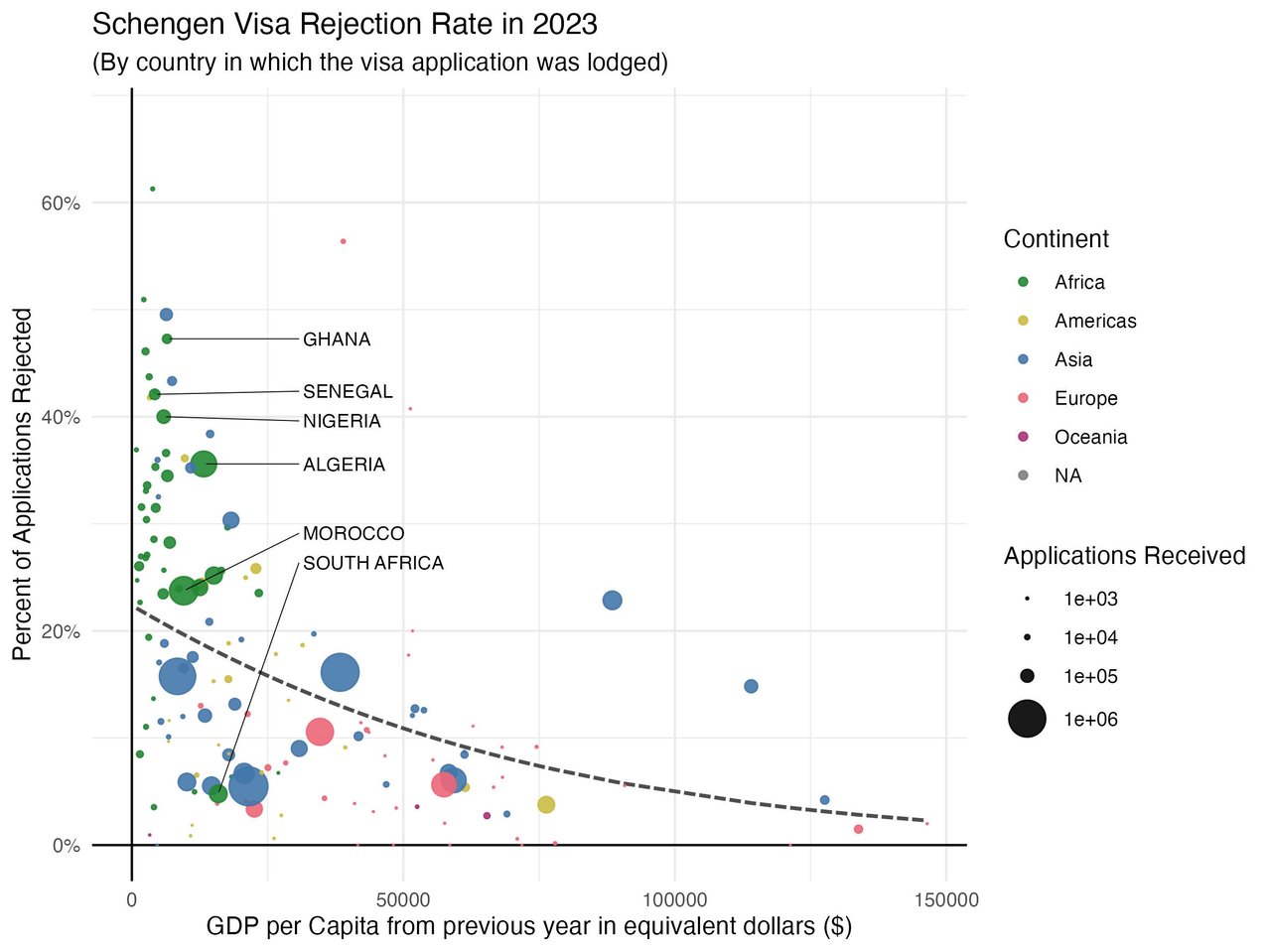

African and Asian countries bear 90 percent of the costs for rejected Schengen visas.

The data also shows that rejection rates of short-term visitor visas to Europe and the UK are higher for low and middle-income countries. African countries, in particular, are disproportionately affected, with rejection rates as high as 40-50 percent for Ghana, Senegal and Nigeria.

The largest number of visa applications to the EU come from Morocco and Algeria, according to the data.

“Visa inequality has very tangible consequences and the world’s poorest pay the price,” Marta Foresti, founder of LAGO Collective and senior visiting fellow at the ODI thinktank, told EUobserver.

“You can think of the costs of rejected visas as ‘reverse remittances’, money flowing from poor to rich countries. We never hear about these costs when discussing aid or migration, it is time to change that,” she added.

For its part, the EU estimates that about half of all irregular migrants within the bloc’s 27 member states result from visa overstays. Last year, over 83,000 people were returned to countries outside the EU, a return rate of 19 percent, according to the EU Commission.

Over the past year, the EU has begun to use visa restrictions as a political tool, using Article 25a of its 2019 visa code — a provision which allows it to apply visa restrictions for countries with low rates of migrant returns.

In April, the EU Council agreed to impose visa sanctions on Ethiopia, including a ban on obtaining visas for multiple entries into EU countries, while diplomatic and service passport holders will no longer be exempt from visa fees.

EU ministers also extended the processing time for visas from 15 days to 45 days, citing Ethiopia's lack of co-operation in the return of its nationals staying illegally in EU countries.

Also in April, EU ministers lifted visa restrictions on Gambia, that had been imposed in 2021, after its migrant return rate increased from 14 percent in 2022, to 37 percent in 2023.

Although the EU has promised to include legal pathways, student and work exchange programmes, and other mechanisms in its trade deals with African states, the focus of a series of recent economic support agreements with Tunisia, Mauritania and Egypt, worth over €8bn has been paying these governments to tighten migration control.

Author Bio

Benjamin Fox is a seasoned reporter and editor, previously working for fellow Brussels publication Euractiv. His reporting has also been published in the Guardian, the East African, Euractiv, Private Eye and Africa Confidential, among others. He heads up the AU-EU section at EUobserver, based in Nairobi, Kenya.

Tags

Author Bio

Benjamin Fox is a seasoned reporter and editor, previously working for fellow Brussels publication Euractiv. His reporting has also been published in the Guardian, the East African, Euractiv, Private Eye and Africa Confidential, among others. He heads up the AU-EU section at EUobserver, based in Nairobi, Kenya.