EU among top spenders on ineffective ‘climate solutions’

EU countries rank high among wealthy countries that spend billions of public money on so-called 'climate solutions' that "consistently fail, overspend, or underperform," new analysis by research and advocacy group Oil Change International (OCI) suggests.

The report focuses on Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) and fossil hydrogen. CCS involves capturing emissions at the source, a technology heavily promoted by gas and oil companies as a way to continue burning fossil fuels.

However, according to the report's authors, despite many decades of research and global public subsidies worth $30bn [€27bn] in the past 40 years, the technology has "failed to make a dent in carbon emissions."

First, the money: since the first test projects came online in 1984, 80 percent have failed due to technical issues, cost overruns, and a lack of financial return.

Of the projects that have received government funding — almost all of which were awarded after 2008 — 45 percent were spent on projects that are no longer operational today.

The US tops the list with $12bn in CCS and hydrogen subsidies. Norway comes in at $6bn, Canada at $3.8bn, the EU itself spent $3.6bn, and the Netherlands at $2.6bn, according to the research.

Together, these four make up 95 percent of all carbon capture and hydrogen subsidies. Now, the second question is: how effective is the technology in the first place?

Here the data compiled by OCI is perhaps even more damning.

The annual capacity of global carbon capture projects today is 51 million metric tons. This is slightly over 0.1 percent of annual global emissions.

More problematic is that after many decades of research, the technology still doesn't come close to working as advertised.

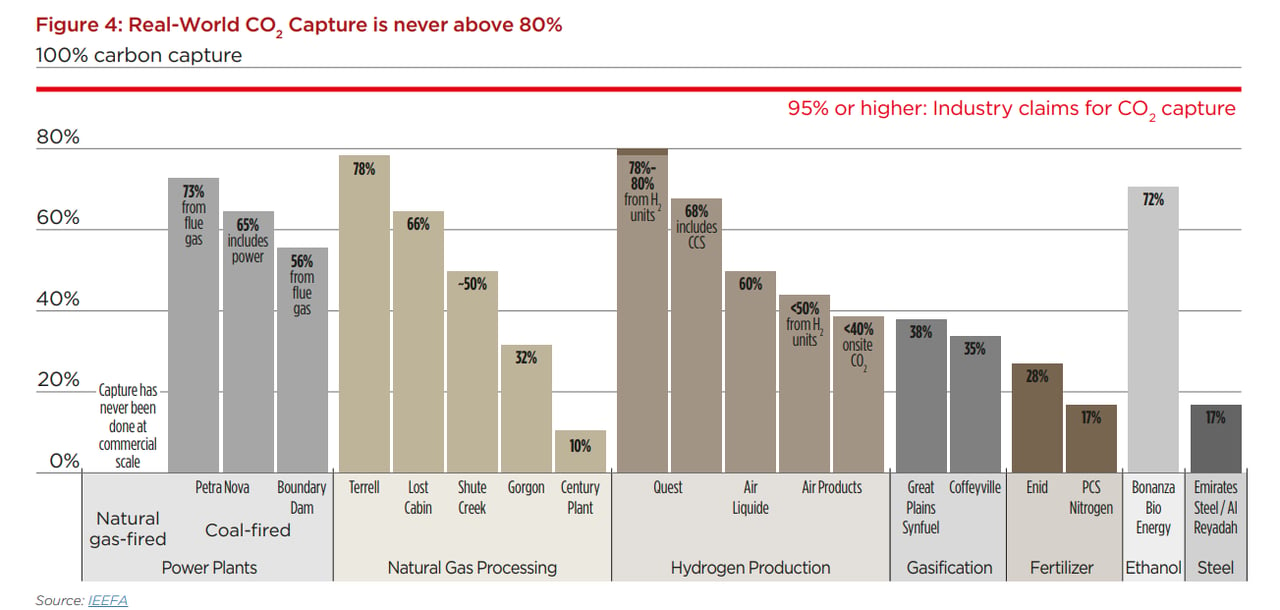

While the industry claims carbon capture can capture 95 percent of emissions, the US-based Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) found that real-world performance is much lower. No plant has captured more than 80 percent.

In some cases, the figure is much lower, dropping to just 10 percent with the carbon sequestration technology used at one plant.

Another recent example is Shell's Quest project in Alberta, Canada. This project captures CO2 from producing hydrogen used to refine tar sands oil, which is a very energy-intensive and polluting process. For this it has received over $600m.

But results have been disappointing, with only 68-percent of emissions captured. Despite this, Greenpeace recently revealed that the oil and gas giant earned an additional €130m on the project through a carbon credit deal with the Albertan government.

The subsidies will "prolong fossil-fuel extraction and enhance the industry's profits" and, in the years to come, "divert away research and investment" from proven alternatives, such as batteries, wind and solar, OCI argues.

Yet oil majors such as Shell and Exxon say more investment is needed to develop CCS, and governments seem to have listened.

OCI tracks between $114bn and $237bn in available public new funds announced since 2020, most of which will come from the US, Canada, and European countries.

"We need real climate action, not fossil fuel bailouts" said OCI on social media.

Author Bio

Wester is a journalist from the Netherlands with a focus on the green economy. He joined EUobserver in September 2021. Previously he was editor-in-chief of Vice, Motherboard, a science-based website, and climate economy journalist for The Correspondent.

Tags

Author Bio

Wester is a journalist from the Netherlands with a focus on the green economy. He joined EUobserver in September 2021. Previously he was editor-in-chief of Vice, Motherboard, a science-based website, and climate economy journalist for The Correspondent.