Investigation

'Cementing over our own future': Europe's nature loss is 600 football pitches daily

Europe is losing green spaces that once sheltered wildlife, supplied food and removed carbon from the atmosphere at an alarming rate, a new investigation reveals.

Today, in the first investigation of its kind across Europe, the Green to Grey journalism project, which worked with scientists from the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research (NINA), can reveal the true extent of lost nature and cropland on the continent.

The cross-border investigation was conducted by Arena for Journalism in Europe and Norwegian broadcaster NRK, together with other newsrooms in 10 countries across Europe.

Using satellite imagery, artificial intelligence and on-the-ground reporting, their project quantifies how much land we are losing to construction.

Every year, Europe loses 1,500km² to construction, their analysis found.

Between January 2018 and December 2023, Europe lost approximately 9,000km² — an area the size of Cyprus. This is close to 30km² destroyed every week, the equivalent of 600 football pitches every single day.

Nature accounts for the majority of these losses, at about 900km² a year. But the research shows agricultural land accounts for 600km² a year, with grave consequences for food security and health on the continent.

These numbers also show that undeveloped land in Europe is disappearing up to one and a half times faster than previously estimated.

New methodology

Until now, the best Europe-wide estimates of nature loss have been based on official figures produced by the European Environment Agency (EEA), using a methodology that only detects large-scale construction projects from satellite imagery.

The methodology Green to Grey developed, however, was able to identify much smaller constructions, as well as many narrow roads and railways.

Reporters found that four-out-of-every-five instances of construction occurred within populated areas already transformed by human activities. These include parks and green spaces in urban areas, essential for recreation, flood regulation and shade as summer temperatures soar.

They also found many examples of precious nature, bulldozed to accommodate commercial activities, luxury homes and tourism. But the most common interventions, accounting for the majority of all cases, were to build housing or roads.

Scientists have long studied the impact of the large-scale destruction of nature in places like the Amazon rainforest. But in Europe, we heard repeatedly that we have relatively little nature left.

The research shows the grave impacts of cumulative small-scale losses of nature and cropland: “It's a slow-burning issue,” says Jan-Erik Petersen, ecosystem expert at the EEA. “It just accumulates over time.”

Guy Pe’er, conservation biologist from the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research and the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research, says: “If we allow these small-scale losses to continuously happen, we risk driving the system to a complete collapse. We are literally risking our health and security.”

In 2021, the EU set a goal to offset land taken for construction with an equal area of nature restoration elsewhere. The “no net land take by 2050” strategy is non-binding, and, the research shows, has so far failed to significantly reduce construction on previously unbuilt land.

No country spared

While the losses are Europe-wide, there are patterns in the data.

In Scandinavia, forests are particularly affected. In southern Europe, coastal areas are being erased. Cropland loss is more prevalent in Central Europe, in places like Germany and Denmark, where nature has been depleted by years of pre-existing developments.

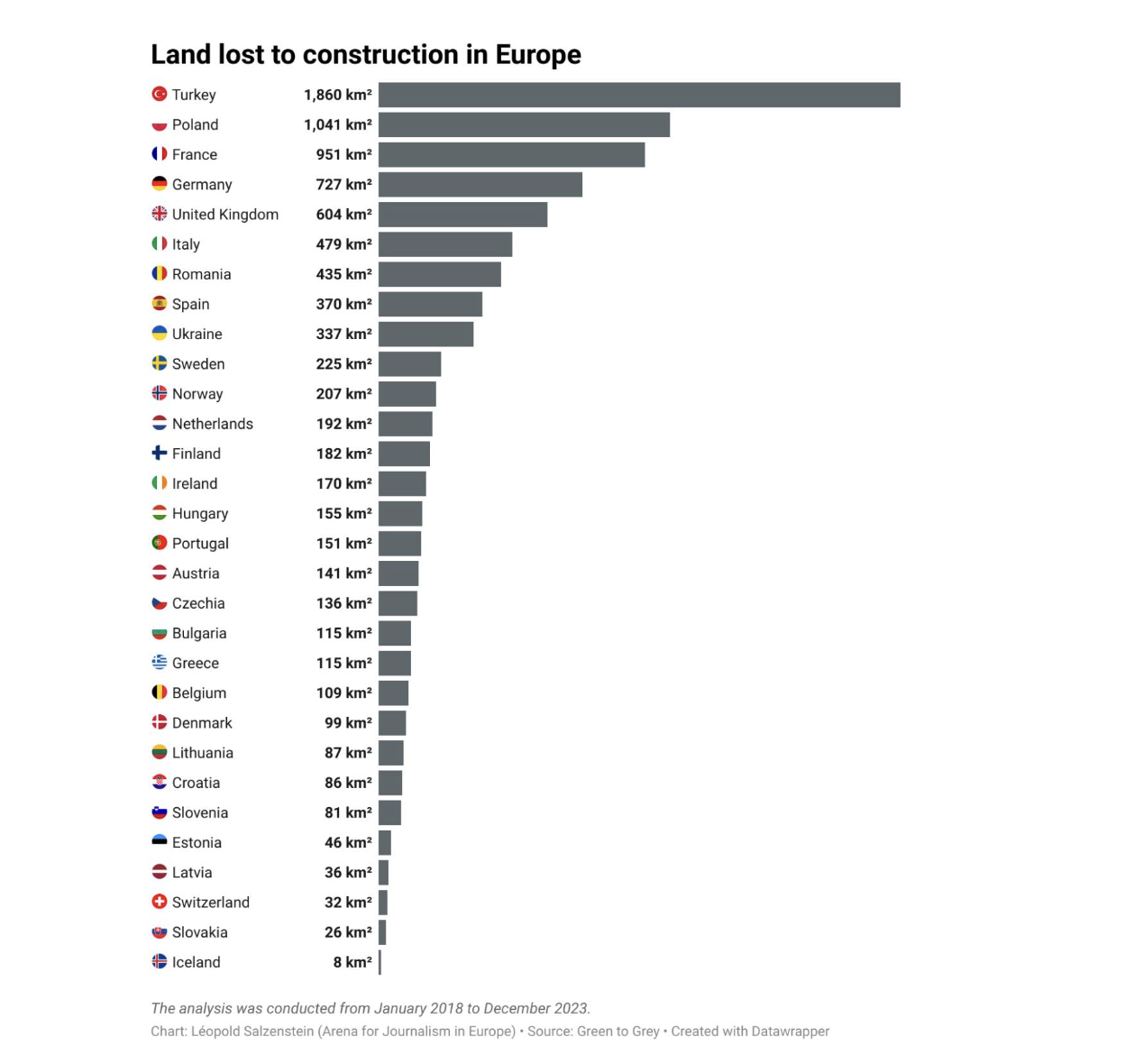

All countries are losing their natural and agricultural areas, but some are losing more than others.

In absolute terms, Turkey tops the list with 1,860km² of nature and cropland lost between 2018 and 2023, an area bigger than Greater London. Poland is next with more than 1,000km² lost, followed by France and then Germany.

If adjusted based on the size of the country, then the Netherlands and Belgium, smaller but more densely populated, come out top. These countries build on a higher proportion of their total surface area each year compared to large countries with fewer inhabitants, such as Norway, Sweden, or Finland.

But if adjusted based on population size, Scandinavian countries fare worse. Norway’s construction translates to roughly six square metres of nature and cropland every year for each resident. In Switzerland, per capita losses are ten times less.

'We cannot live in a stone desert'

In Italy, reporters discovered that Lake Garda, a world-famous biodiversity hotspot, is being overrun with developments in the name of 'sustainable tourism'. In Poland, investment properties have popped up around land intended for protection by the EU. In Finland, areas of endangered nature were turned into a highway.

“You hear all the time that, ‘Oh, we gave this building permission because it was only 2,000m², so what?” But if you add up all those permissions all over Europe, it’s a lot.”

Reporters investigated a golfing resort sprawling across a nature reserve in Portugal and a harbour for luxury yachts sunk into a wetland in Turkey. Alongside these major developments, in Lapland, they found the kind of small-scale interventions that are more common. Multiple tiny encroachments to service the desires of tourists, each one making a dent in the pristine nature that those same tourists come to see.

The investigation showed it is the small-scale losses that really add up.

Peter Verburg, professor in environmental spatial analysis at VU University Amsterdam says that the cumulative impact of many tiny developments is leading to global change: “You hear all the time that, ‘Oh, we gave this building permission because it was only 2,000m², so what?” But if you add up all those permissions all over Europe, it’s a lot.”

Building on habitats means losing not just animals or native plants, but also crucial natural defences against extreme weather and rising temperatures.

More buildings bring more heat and a higher risk of flooding, at a time when Europe, along with the Arctic, is warming faster than any other continent.

Gunnar Austrheim, professor in biology at NTNU in Trondheim, co-authored an IPBES report which concluded in 2018 that Europe and central Asia were facing a crisis that would require profound societal changes to change course. Our investigation, he says, shows that politicians failed to act, instead embracing “business as usual”.

'Cementing over our own future'

Lena Schilling, a Green MEP, says that every forest, fertile field, and biodiversity hotspot destroyed for short-term profit is a betrayal of the promises we made to young people.

“For years, the EU has promised to lead on climate and nature protection, but what this investigation shows is that we are literally cementing over our own future,” she says.

In 2024, the EU approved the Nature Restoration Regulation – a pioneering law that aims to revive 90 percent of degraded habitats across the EU by 2050.

For the first time, national governments are obliged to set deadlines and meet targets on nature conservation.

The regulation has faced intense pushback from the farming and forestry sector. Questions remain about how these measures will be financed and enforced, as the EU has promised to cut red tape for businesses and has rolled back a number of its ambitious environmental goals in the past year.

Existing laws protecting nature might be next on the chopping board, warn environmental NGOs responsible for a petition, signed by 200,000 EU citizens, calling for current measures to be maintained.

Meanwhile, forthcoming EU soil legislation makes no commitment to “no net land take by 2050”.

In September, the European Environment Agency admitted in its state of the environment report that the EU target of no net land take by 2050 is unlikely to be met.

Peter Verburg from VU University Amsterdam says that to reach no net land take by 2050, European countries need intermediate, legally-binding goals.

“This determines our future, we cannot live in a stone desert,” Verburg says. “We need green space. We need to see trees. We need nature to support us, especially with climate change.”

Every month, hundreds of thousands of people read the journalism and opinion published by EUobserver. With your support, millions of others will as well.

If you're not already, become a supporting member today.

Author Bio

Zeynep Şentek is a Turkish investigative journalist focused on corruption, human rights, and environmental issues.

Jelena Prtorić is an investigative journalist covering migration, climate, social movements and gender across languages.

Hazel Sheffield is a UK-based multimedia and investigative journalist, founder of Far Nearer, writing on business, alternative economies, and the environment.

Léopold Salzenstein is an investigative data journalist in France.

Related articles

Tags

Author Bio

Zeynep Şentek is a Turkish investigative journalist focused on corruption, human rights, and environmental issues.

Jelena Prtorić is an investigative journalist covering migration, climate, social movements and gender across languages.

Hazel Sheffield is a UK-based multimedia and investigative journalist, founder of Far Nearer, writing on business, alternative economies, and the environment.

Léopold Salzenstein is an investigative data journalist in France.