Opinion

2000-2024: A short history of Europe's far-right...so far

The 4 February 2000 might as well be remembered as the day Europe had to fight again for its democratic values. And it failed.

On that day, in Austria, the center-right ÖVP, a member of the European People’s Party (EPP), announced a coalition with the radical-right FPÖ.

The reaction was broad and strong. In the streets of Vienna several demonstrations took place. The German government called it an “historic mistake” and the Portuguese presidency of the European Union said that “racist and xenophobic behaviors” were taking power in Austria.

All EU states suspended their normal bilateral relations with Austria, reducing them to the minimum possible, while the European institutions showed unease with the fact that they had to treat Austria with equality while it had ministers who were the successors of Nazism.

The president of Austria felt forced to have the new chancellor and its deputy sign a declaration that they vow to respect human rights, the principles of a pluralist democracy and the rule of law. Israel withdrew its ambassador from Vienna and announced unprecedented diplomatic sanctions, warning that in the birthplace of Hitler deniers of the Holocaust had taken power.

By September 2000, all EU states had lifted their sanctions. The Austrian far-right won their fight for normalisation, and all European Union states recognized it as legitimate government. The government of alliance of the democratic and authoritarian right would last until 2007.

Enter Silvio 'Bunga Bunga' Berlusconi

This wasn’t the first time, as in 1994 Silvio Berlusconi had made a coalition with what is now Giorgia Meloni’s Fratelli d’Italia, then under Gianfranco Fini. And even earlier, in the first decade of the new West German government, the far-right parties German Party (BP) and All-German Bloc/League of Expellees and Deprived of Rights (GB/BHE) had ministers under Konrad Adenauer’s government.

But while those examples were easily ignored as small partners in governments strongly led by the center-right, the Austrian example was a clear 50:50 partnership that was difficult to ignore.

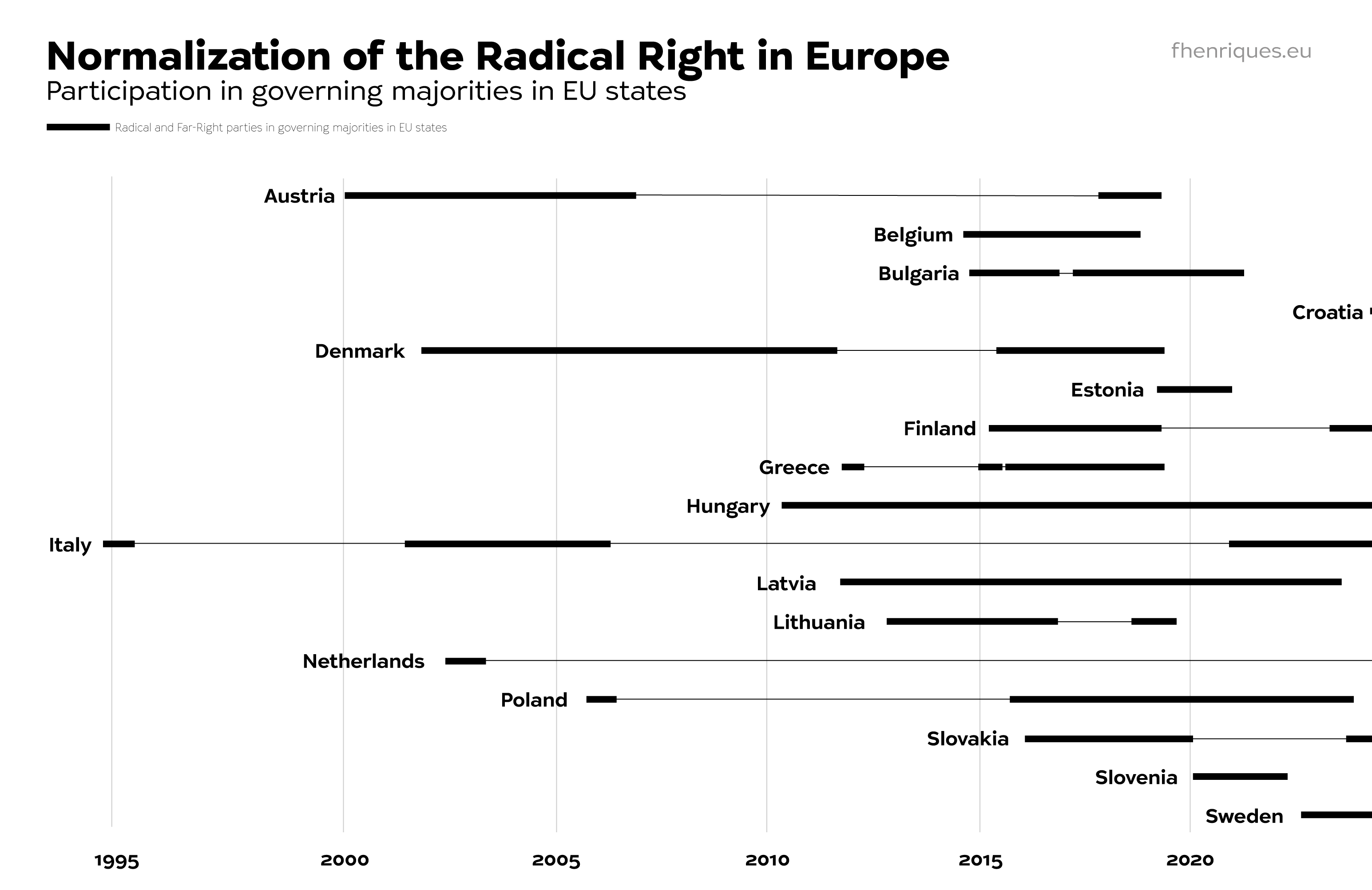

Yet, after the normalisation of the Austrian participation of the far-right in national government, it became acceptable all over Europe. Across the whole continent there are now more countries the centre-right has either brought the far-right into power or where it radicalized itself to become the far-right, than countries where the cordon sanitaire is still standing.

One year after Austria, also Denmark normalized its far-right with a liberal-conservative government counting on the parliamentary support of the far-right Danish People's Party.

And the year after was the time for a coalition of liberals, conservatives and the far-right in the Netherlands. Then Poland, Hungary, Greece, Latvia, Belgium, Bulgaria, Finland, Slovakia, Estonia, Slovenia, Croatia.

We reach 2024 with most EU states having had the far-right involved in power than those that have not

In each of these countries the center-right had to decide between the most basic democratic values, or the shortest way to power. And in each case they chose the shortest way to power.

By accepting the far-right as a partner, they not only normalized those parties, and in many cases made them one of their strongest electoral opponents, but also normalised their policies. The differences between mainstream politics and the far-right stopped being a question of different systems but of quantitative differences within the same system.

Under Manfred Weber and Ursula von der Leyen this strategic choice has been brought to the European level. The first part was to adopt many of the ideologic flags of the far-right.

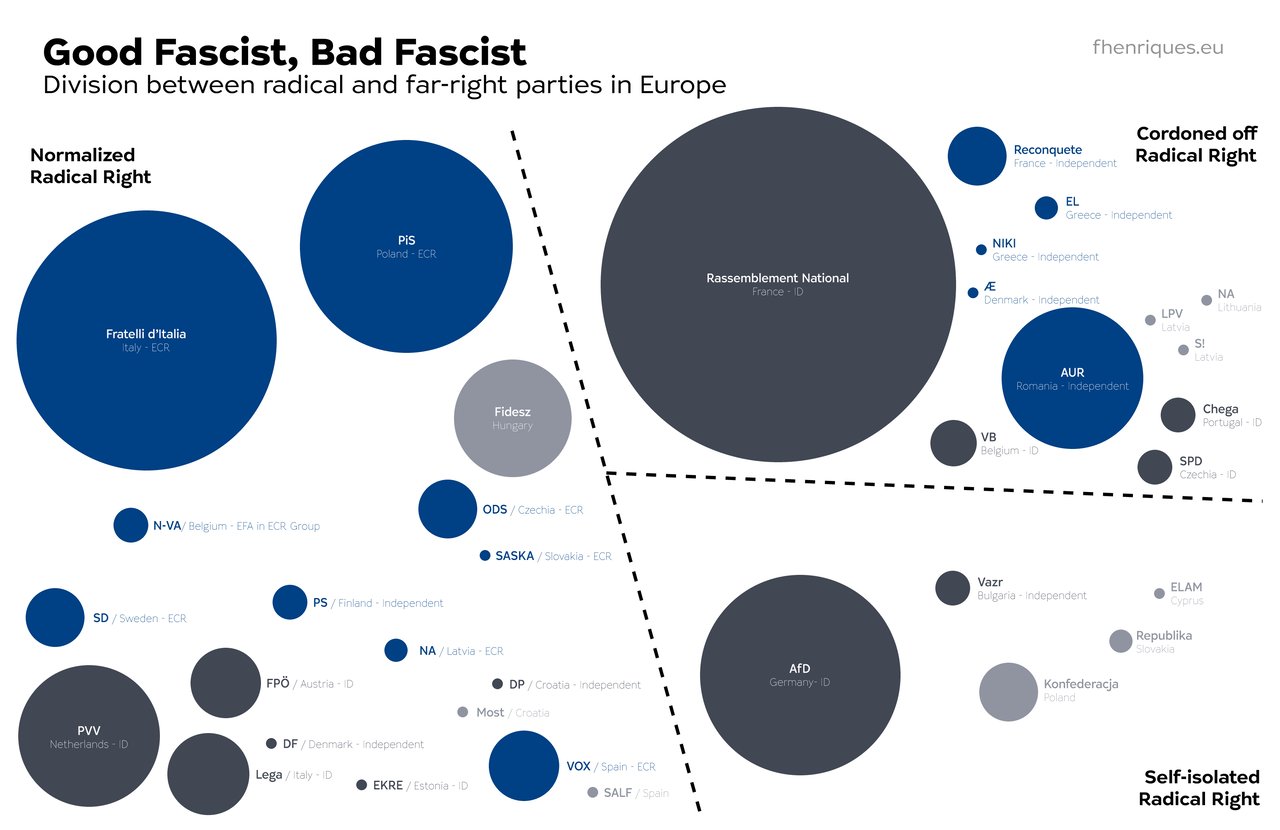

From migration to climate action, the EPP changed their own stance in order to copy the far-right. Then it made a clear division between what it considers good fascists and bad fascists. Half of Europe’s radical-right parties are now normalized, with parties like Fratelli d’Italia in Italy, Fidesz in Hungary and the ODS in Czechia running their respective countries in coalition with the EPP, while the other half is either behind an imposed cordon sanitaire – like France’s Rassemblement National – or happily behind such a wall – like Germany’s Alternative für Deutschland.

Finally the big problem is that not much will change after the European Elections. There will be no majority in the Council or the Parliament that passes through an alliance of the EPP and the parties to its right. What will happen is what always happened before, a grand coalition of EPP, Socialists and Liberals.

With one difference: the playing field has been rigged.

The policies and tactics of the far-right have been normalized, the EPP has moved to the right and with it brought all other parties. The next commission will have far-right commissioners from Italy, Hungary and the Netherlands and Von der Leyen will have no issues giving them relevant portfolios. The transformation of the nascent European democracy into an authoritarian project might have started in Austria in the year 2000, but 24 years later has never been stronger.

Author Bio

Filipe Henriques is a Brussels-based political scientist & analyst focused on European politics.

Related articles

Tags

Author Bio

Filipe Henriques is a Brussels-based political scientist & analyst focused on European politics.