Analysis

Has the ECB's rate policy been a success?

The European Central Bank (ECB) is expected to start lowering interest rates by 0.25 percent on Thursday (6 June). This will reduce the main interest rate from a multi-decade high of four percent down to 3.75 percent, reducing the lending costs for households and businesses, which could result in a slight uptick in economic activity.

This brings to an end one of the steepest and most impactful series of rate hikes in post-war European history, which makes it an interesting moment to look back, at how it has impacted the economy as a whole and wage earners specifically and at some of the arguments that have emerged from it.

For the time being, lending rates will still remain high. And few expect rates to fall to the sub-zero levels of the pre-pandemic era anytime soon. With overall prices now only 2.6 percent higher in May compared to last year, the bank is fast approaching its two-percent inflation target.

So, one of the hotly-debated questions amongst economists now is how far and by how much interest rates will fall from here.

Disagreement

It's necessary to briefly look at some of the arguments which vary wildly. Some ECB hawks, such as Austria’s Robert Holzmann, fear inflation could pick up again, as inflation actually increased a little last month compared to April’s 2.4 percent.

This is mainly driven by services like hospitality – not energy or goods – partly related to an uptick in wages in Europe in the first quarter of 2024. Therefore, this week, he said he would only agree to one rate decrease.

Other rate-watchers however, like Robin Brooks, a senior analyst at the Brookings Institute, a Washington-based institute, have consistently warned that the eurozone is headed for deflation. He believes the ECB should “never have increased borrowing costs in the first place” because there “never was demand-led inflation” in Europe.

To most, this may seem like a dry debate about interest rates at first glance. But it is a fundamental critique of the ECB’s rate policies, and it prompts the question: who should bear the cost of inflation in the first place?

Supply-shock

This is a difficult debate to make sense of — because many of the arguments used by those critical of the ECB are often also used by the bank's own senior management.

As ECB president Christine Lagarde has admitted on many occasions herself, raising interest rates won’t change energy prices.

This is because supply issues in the energy and food sectors caused prices to rise. Record corporate profits then kept prices high after the initial shock. Yet all of these price-drivers are not affected by higher interest rates, which is a tool aimed at lowering consumption and demand from businesses and households.

Therefore, many like Brooks raised the question: Why increase rates in the first place?

The ECB's reasoning evolved somewhat, but in 2023, it solidified around the idea what had started as a supply shock in the energy and food sectors somehow morphed into a mixture of supply and excess demand.

But this argument was questioned from the very beginning. Erik Fossing Nielsen, chief economist at Unicredit, found it “extremely unlikely” demand had anything to do with it and noted in one of his weekly monetary wrap-ups that personal consumption in the eurozone was a “stunning” 0.8 percent below 2019 levels in real terms.

Some conservative lobby outfits continue to blame inflation on the monetary stimulus during the Covid-19 pandemic. But especially in Europe there is no proof monetary support has resulted in "too much money is chasing too few goods" as the neoliberal economist Milton Friedman once described it.

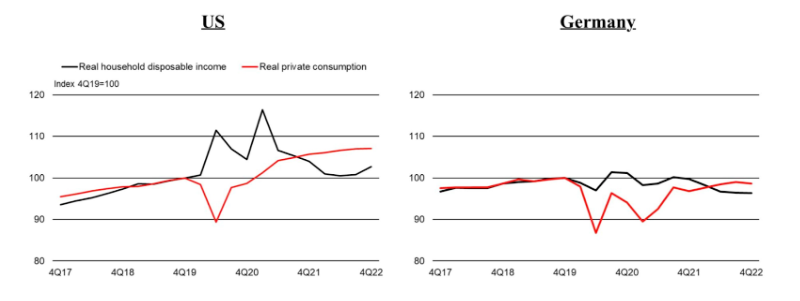

Financial historian Adam Tooze — who described the ECB’s rate policies as a “blunt force, high-risk policy” in one of his Chartbook newsletters last year — shared a graph that drove home the vast difference between US household spending, which has steadily increased, and German consumption, which has stagnated since 2017 and shows no signs of recovery.

Indeed, it has now become abundantly clear from the ECB’s own data that wages — a core mover of demand — have done little to push up prices, suggesting that inflation in the eurozone was supply-driven rather than demand-driven.

Since interest rates address domestic demand, not supply, the decision by the bank's governing council to commit to the steepest increase in lending rates in its history regardless, remains a point of heavy contention to this day. But more on that later.

Let's first look at some of the consequences

The first thing to say is that some of the worst fears raised by critics of the ECB’s rate policies have not come to pass.

Unemployment has not increased, as many expected. According to commission figures, eurozone unemployment is lower today (6.4 percent) than it was in 2019 (7.5 percent). However, that is not to say the ECB’s rate impact has been mild.

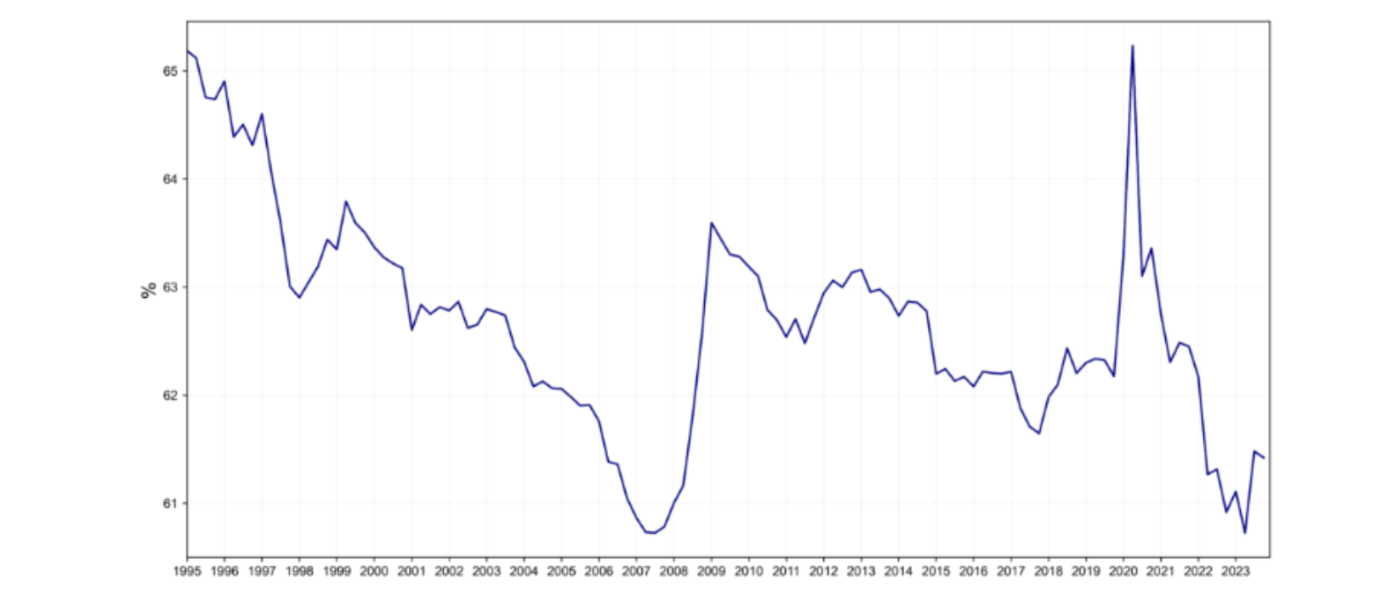

Although there are signs of recovery, prioritising classic wage-restraint policies by raising interest rates has done little to prevent the steepest drop in wage share in recent history (wage share is the portion of GDP allocated to workers).

From fear of uncontrolled wage increases in response to higher prices, the ECB erred on the side of caution, tightening the money supply to prevent wages from rising. However, it largely failed to even mention the core driver of inflation until after the fact. Lagarde later admitted that two-thirds of inflation was related to profits (the usual share is one-third).

Another consequence of the ECB’s policy, not eagerly discussed by the bank’s management, is that high rates have enabled record rates-profits on EU commercial bank deposits, whose boards gave shareholders a record pay-out of €120bn in 2023 alone.

Already last year, some MEPs on the green-left side of the political aisle criticised Lagarde — who was hard-pressed to explain how such excess fitted into the ECB’s overarching narrative of belt-tightening.

Many have noted that demand for loans cratered in 2023. This has hampered business investments in machinery and people which are needed to remain competitive. Dutch central banker Klaas Knot made clear in a recent interview that this decline in lending “was a feature not a bug” of monetary policy.

But when historic bank profits are also a ‘feature, not a bug’ of ECB policy, one starts to wonder if current rate policies are still fit for purpose.

Rasmus Andresen, a German Green MEP in the EU Parliament’s monetary affairs committee and the rapporteur for the parliament’s annual report on the ECB in 2022, has described the ECB’s policies as “very damaging” for German industry.

Furthermore, ECB critics have pointed out that high borrowing costs have also undermined investments in renewables. This is because wind and solar projects are almost exclusively loan-funded (as opposed to gas and oil projects, which are more often paid upfront). This has had dire effects on some of the biggest players in the renewables sector.

Central bankers rarely speak of this widely-acknowledged fact. This is not to say the problem isn’t on their radar. Speaking at an economics festival in Trento in May, Piero Cippolone, the Italian central bank chief, described the massively-increased cost of the green transition as a “tragedy on the horizon” – Europe’s next great problem to solve.

In March, Cipollone called for rates to be “dialled back swiftly.” But in terms of policy solutions, central bankers have so far seen fit to shift responsibility to governments, which remain largely silent on the effects of interest rates on renewables.

"As I speak, the private sector benefits from the same interest rates whether it finances renewables, gas or coal. This is totally absurd," French president Emmanuel Macron said about the impasse in December. But he has been the exception.

Most in the higher echelons of government policy — protective of central bank independence as they are — have been reluctant to critique ECB rate policies, leading to a policy vacuum at the heart of European economic policymaking that has done little to spur public debate on the issue.

This is remarkable. It is a harsh fact that the EU is now largely back on the same low-growth trajectory it started four years ago. Not all of this is a consequence of interest rates. But it is no wonder experienced rate-watchers like Brooks question whether lowering economic activity is the right tool in such an environment.

Since its beginning, monetary strategy has been sold to the public as a difficult trade-off between curbing surging prices and economic growth. While inflation is indeed now lower, the ECB has offered little evidence of effectiveness.

Have they been effective?

Returning to Thursday's rate discussion, the question of their general effectiveness remains open.

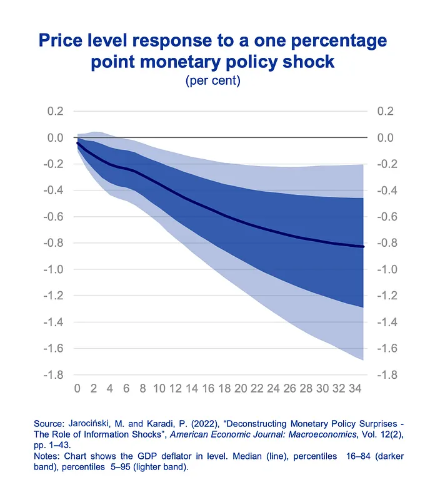

According to a benchmark model cited by ECB economists, the impact of a one-percent rate hike on inflation after one year ranges from a low 0.1 percentage point to as much as 0.8 percentage points.

Despite widely differing rate policies, inflation trajectories have been “the same across the globe,” Gianluca Benigno, a macroeconomist and professor at the University of Lausanne, recently remarked on social media.

As Tooze noted in his substack newsletter, uncertainty over the effects of rates on inflation becomes an argument to “double down” on it.

This may seem illogical but it is firmly rooted in the ECB’s stated policy that signalling a strong rate response to inflation thus “anchors” inflation expectations in society—simply said: if workers and businesses know the central bank has taken strong action, they expect inflation to come down, adjusting wages along with it.

As the ECB’s own explainer notes, “it’s easily understood.” This may be true. There is just one problem: people don't seem to really base their expectations on central bank actions.

The latest example of this came out of a survey conducted in May by the Social Economics Lab, a research initiative connected to Harvard University.

The results coming out of the questionnaire showed that over half of the respondents believe that inflation will increase following an increase in interest rate — the exact opposite of what central banks are aiming to achieve.

Maybe listen to the people more?

The surveyed group consisted of US citizens, so the results may be different in Europe. However, it is interesting to note what people think are effective ways to curb inflation when asked in simple terms.

All central banks, whether the United States Federal Reserve or the ECB, have sold their rate policies to the public as a difficult trade-off between two evils: high inflation and lower economic growth.

But when asked simply, in non-abstract language, very few people surveyed by the Social Economics Lab think it is necessary for central banks to dampen demand or increase unemployment to reduce inflation.

Conversely, there is a lot of support for policies to help low-income households cope with inflation, such as cash transfers, food stamps or income support (as happened in most EU countries during the Covid pandemic and the early days of the energy crisis).

There also is a lot of support for measures that target corporate profits directly and for measures to freeze the prices of essentials.

Another poll by the US-based think-tank Data for Progress showed similar results: 69 percent of voters believe the government should do more to regulate grocery stores that raise prices to maximise profits.

Whatever the right mix is, it is doubtful that protecting people against future price shocks — which ECB central bankers assume will become more frequent, as a consequence of, among other things, climate change — should predominantly or exclusively “demand-driven” (through wage restraint and higher unemployment), as Dutch central banker Knot believes.

If people had more of a say, it would probably consist of a wider range of measures and tools that seek to limit the impact of inflation prices on workers rather than magnify it.

And maybe those people would have a point.

Author Bio

Wester is a journalist from the Netherlands with a focus on the green economy. He joined EUobserver in September 2021. Previously he was editor-in-chief of Vice, Motherboard, a science-based website, and climate economy journalist for The Correspondent.

Tags

Author Bio

Wester is a journalist from the Netherlands with a focus on the green economy. He joined EUobserver in September 2021. Previously he was editor-in-chief of Vice, Motherboard, a science-based website, and climate economy journalist for The Correspondent.