Investigation

France spearheaded successful effort to dilute EU AI regulation

This story is produced by Investigate Europe, a cross-border team of journalists based across the continent. The investigation is being published with media partners including Disclose (France), EUobserver (Belgium), Il Fatto Quotidiano (Italy), InfoLibre (Spain), Netzpolitik (Germany), Publico (Portugal) and Efsyn (Greece).

In a matter of days, governments across the EU will have the power to deploy AI-powered technologies that track citizens in public spaces, conduct real-time surveillance to monitor refugees in border zones and use facial recognition tools against people based on their suspected political affiliations or religious beliefs.

These are just some of the loopholes and national security exemptions forced through in the European Artificial Intelligence Act, the world’s first set of laws targeting the sector.

The law is designed to mitigate the myriad bias and privacy fears surrounding the use of AI technologies and algorithms, with the EU saying the law will create “an AI ecosystem that benefits everyone.”

But several controversial parts of the regulation will take effect from 2 February 2025, thanks in part to secret lobbying by France and a host of European states.

Internal documents obtained from the negotiations by Investigate Europe reveal member states successfully campaigned to dilute measures, giving police and border authorities, among others, greater freedoms to covertly monitor citizens.

“In a series of bureaucratic loopholes and omissions, the AI Act falls short of the ambitious, human rights protecting legislation many hoped for,” said Sarah Chander, co-founder of Equinox Initiative for Racial Justice. “In reality, the legislation is a pro-industry instrument designed to fast track Europe’s AI market and promote the digitalisation of public services.”

Investigate Europe analysed more than 100 documents from behind-closed-doors meetings of ambassadors from the 27 member states, the so-called Coreper, in the EU Council and spoke to multiple sources present at the negotiations.

These meeting minutes and accounts from across the political spectrum detail how France strategically engineered amendments to the regulation.

The use of AI in public spaces is broadly prohibited under the act, but changes pushed for by the French president Emmanuel Macron administration and others mean that law enforcement and border officials will have the ability to bypass the ban.

Climate demonstrations or political protests, for instance, could now be freely targeted with AI-powered surveillance if police have national security concerns.

'At all costs'

When EU ambassadors met on 18 November 2022, France’s representative was unequivocal about the country’s wishes, according to meeting minutes obtained: “The exclusion of security and defence … must be maintained at all costs.”

It was a reference to a part of the law proposing that only the military would be allowed to conduct surveillance in public spaces. France wanted an exemption for all authorities if necessary for ‘national security’.

Climate demonstrations or political protests, for instance, could now be freely targeted with AI-powered surveillance if police have national security concerns

At a later meeting, Italy, Hungary, Romania, Sweden, the Czech Republic, Lithuania, Finland and Bulgaria all expressed support for the French position.

"This battle was one of the toughest and we lost it,” reflected a source in the European Parliament involved in the negotiations, who asked to remain anonymous.

In the final text, there are no longer any restrictions on the use of surveillance in public spaces — the need for a national agency approval or declaring the product in a public register — if a state deems it necessary on the grounds of national security.

In practice, these exemptions will also cover private companies — or possibly third countries — that provide the AI-powered technology to police and law enforcement agencies. The text stipulates that surveillance is allowed “regardless of the entity carrying out those activities”.

“This article [2.3] goes against every constitution, against fundamental rights, against European law,” a jurist from the centre-right EPP group in the European Parliament said, speaking anonymously. “France could for instance ask the Chinese government to use their satellites to make pictures and then sell the data to the French government.”

The exemption also goes against rulings from the European Court of Justice in 2020 and 2022, says Plixavra Vogiatzoglou, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Amsterdam.

The judgements found French telecommunications companies had breached EU law by retaining customer data on national security grounds.

“The EU court said that private companies involved in national security activities are not exempted, they are still subject to EU law, and the national security exception has to be interpreted very restrictively and the member state has to really justify,” Vogiatzoglou said.

France’s private lobbying in EU Council meetings mirrors its public push to exploit the technologies. In May 2023 the country’s constitutional court sanctioned the use of AI-powered video surveillance during the Paris Olympics.

The move was the first of its kind in the EU and described as “a serious threat to civic freedoms and democratic principles” by Amnesty International. Now, such methods could be rolled out across the bloc.

Emotional recognition systems

The final agreed AI Act, first presented by the European Commission in April 2021 and fought over from the start, has become littered with exceptions.

The use of emotional recognition systems — technologies that interpret people’s moods or feelings — is banned from 2 February in workplaces, schools and universities.

Companies will be prohibited from tracking customers in-store to analyse buying intentions, for example, and employers can not use the systems to scrutinise if staff are happy or likely to leave.

But thanks in part to the lobbying by France and member states, the systems are permitted for all police forces and immigration and border authorities. It is still not clear whether the systems will also be allowed for recruitment personnel, for example, companies to assess applicants for a job.

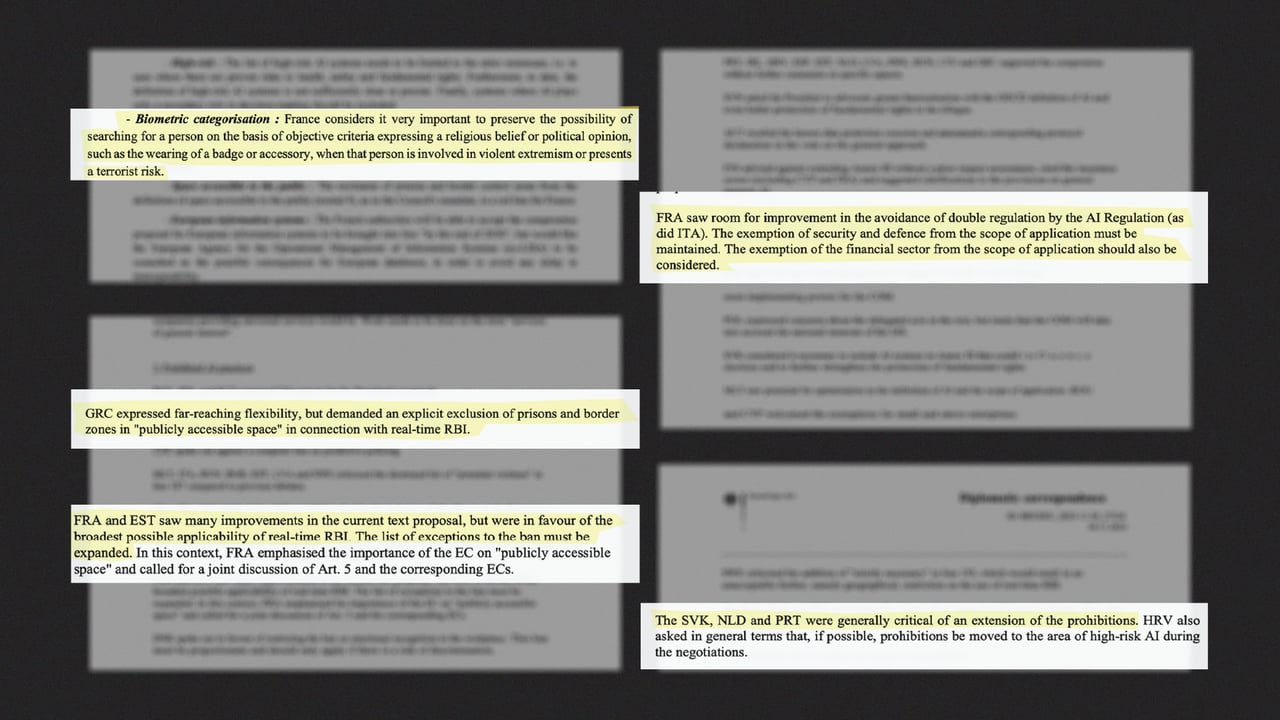

During a meeting on 29 November 2023, Denmark’s ambassador said that any ban “must be proportionate and should only apply if there is a risk of discrimination”. The Netherlands, Portugal and Slovakia took a similar stance in that meeting, with all “generally critical” of widening prohibitions to include law enforcement.

And then there are biometric identification systems used to determine race, political opinions, religion or sexual orientation and even if someone is part of a trade union. These are banned under the act, but there is an exception. Police will be free to use the systems and collect image data on any individual or buy data from private companies.

France again was a driving force.

A document sent on 24 November 2023 by the French government to the Council said it was “very important to preserve the possibility of searching for a person… expressing a religious belief or political opinion, such as the wearing of a badge or accessory, when that person is involved in violent extremism or presents a terrorist risk.”

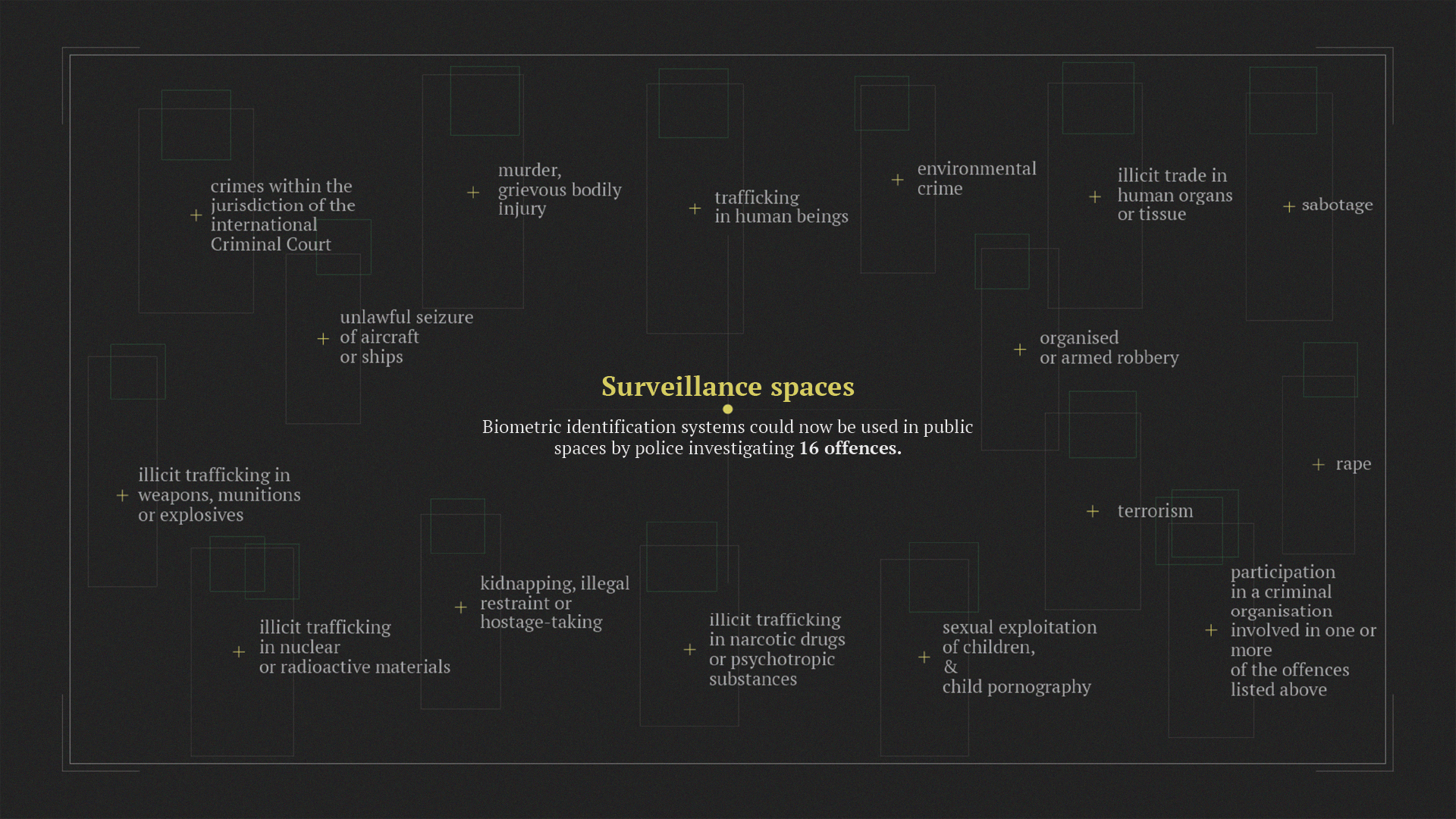

Moreover, facial recognition software can be used in real-time if “strictly necessary” for law enforcement. It can be used by police investigating 16 specified crimes, including a general reference to “environmental crime”. But several states wanted dozens more added to the list.

Minutes from the Coreper meeting in late November 2023 reveal France, along with the ambassadors from Italy, Cyprus, Estonia, Latvia, Bulgaria and Hungary all pushed for the scope to be expanded.

Greece, a country at the forefront of migrant arrivals to Europe in recent years, was another in favour. In the same meeting, its ambassador “demanded an explicit exclusion” for prisons and border zones from any ban, lobbying for authorities to have the power to conduct real-time biometric analysis in public spaces on citizens and refugees and asylum seekers.

The end of anonymity

Biometric systems could now be deployed to surveil millions of faces and cross-check against national databases to identify individuals. Use of the technology in public spaces “means the end of anonymity in those places”, the European Digital Rights Network warned back in 2020.

Civil society and NGOs have long sounded the alarm about the harms that could come from the act, which arrives in the wake of the Pegasus spyware scandal and revelations that discriminatory welfare algorithms have been used by various countries around Europe.

“Ultimately, we are living in a climate where our governments are pushing for more and more resources, laws and technologies to facilitate the surveillance, control and punishment of everyday people,” Equinox’s Sarah Chander said. “And further away from a future where resources could instead be spent on social provision and protection instead of surveillance technology.”

Another loophole carved out concerns predictive policing — the ability of an algorithm to predict who will commit a crime. Spain, which held the presidency of the council as negotiations neared their end in late 2023, already uses predictive policing algorithms. It is the only EU country to admit to doing so, along with the Netherlands.

“Predictive policing is … an important tool for the effective work of law enforcement,” the Spanish ambassador said in a Coreper gathering in October 2023. At a meeting a month later, Ireland, Czech Republic and Finland echoed similar views, pleading against a complete ban on predictive policing products. The final text allows the systems to be used, as long as there is human oversight of the technology.

When the final trialogue between the council, the parliament and the commission began on 6 December 2023, the Spanish presidency was eager to finalise the text prior to the European elections and the anticipated rise of far-right parties and before Viktor Orbán’s Hungary took on the presidency six months later.

Negotiators were locked in a room for a day-and-a-half, an official present at the discussions, who requested anonymity, recalled. “We were exhausted, and only after a night of negotiations did we start talking about the prohibitions at 6 am,” they said. “[In the end] we achieved that every product would be authorised by an independent national authority.”

Self-certification?

And so the use of so-called ‘high risk’ technologies will be subject to requirements, like a court authorisation, registration in a European database and an impact assessment for the respect of fundamental rights.

But even this comes with a caveat. An article was added allowing companies to fill in a self-certification and decide if their product is ‘high risk’ or not, thus potentially freeing them from certain obligations.

An internal working document from the European Parliament’s legal service obtained by Investigate Europe questioned the decision. “A high level of subjectivity left to companies, which appears to be in contrast with the general aim of the AI Act, to address the risk of harm posed by high-risk AI systems.”

The need to keep corporate interests on the side has concerned member states, notably France which is home to a number of leading companies, including Mistral AI.

In a Coreper meeting on 15 November 2023, the French delegation warned that if wider use of the technologies was not permitted, “there was a risk that companies would relocate their business to regions where fundamental rights did not play a role”.

The French government did not respond to requests for comment by the time of publication, nor did the governments of Greece, Portugal or Italy.

Only time will tell how the AI Act is implemented.

Anton Ekker, a Dutch lawyer for digital rights, believes the exemptions will have little impact in practice. “I'm very critical about the use of algorithms by a state. However, the narrative to say that because there are exceptions then things are allowed, it's not correct,” he said. “There are many national, constitutional laws, protecting fundamental rights.”

Professor Rosamunde van Brakel, who teaches legal, ethical and social issues of AI, at the Vrije Universiteit Brussels, however, says national accountability mechanisms may not bring much solace to those impacted by the technologies.

“In most cases regulation and oversight … only kicks in after the violation has taken place, they do not protect us before,” she said. “Moreover AI applications used in the public sector often affect vulnerable populations who are not empowered to launch a complaint or trust that a complaint will be taken seriously.”

Author Bio

Maria Maggiore, Leila Minano and Harald Schumann are journalists from Investigate Europe.

Tags

Author Bio

Maria Maggiore, Leila Minano and Harald Schumann are journalists from Investigate Europe.